August 29, 2016

The share of employees with union representation has been steadily declining for the past three decades. Because unions are one of the most important institutions within the political sphere for non-elites to advance their interests — higher wages, better work conditions, hours, benefits, etc. — this is unfortunate. Unsurprisingly, the dramatic decline in union representation since the 1980s has been accompanied by widening economic inequality.

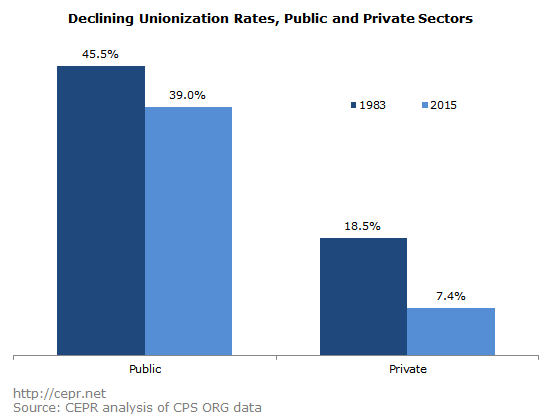

The private sector, accounting for roughly 85 percent of those employed in 2015, has experienced the largest decline in employees represented by a union, down just over 11 percentage points from 1983 to 2015. This dramatic decline means fewer workers have the opportunity to advocate for their interests. Unionization rates in the public sector have declined as well, though at a significantly lower rate (down 6.5 percentage points, from 45.5 percent in 1983 to 39 percent in 2015). Technological advances and a more global economy are less the cause of this decline than legislation that purposefully weakens unions and employers’ unfavorable attitudes towards unions.

In terms of legislation, over half of states — the majority of them dominated by Republicans — have passed “right-to-work” legislation, and the number continues to grow. Right-to-work laws undermine a union’s ability to collectively bargain by making it so that any employee who chooses to not to join a union can get the benefits guaranteed by a union contract without having to pay a representation fee. Despite arguments that right-to-work laws will promote job growth and boost local economies, they have done little to improve the wages of workers or support job growth in the states that have them, and actually increase wage inequality. In 2015, seven out of 10 states with the highest unemployment were states with these laws. In addition to right-to-work legislation, many employers create a work environment that is hostile to union organizing. For example, a CEPR report found “significant support for the view that an important part of the decline in private-sector unionization rates … is that aggressive — even illegal — employer behavior has undermined the ability of workers to create unions at their work places.”

The decline of unions is not a result of autonomous economic forces; there are clear legislative and managerial actions that have purposefully, and so far successfully, chipped away at the membership of unions. This means lower wages, fewer benefits, and widening inequality. When talking about unions, the topic doesn’t just include declining wages, benefits, and job security. It’s also the decline of an institution that historically serves the interests of working people.

Check out CEPR’s latest paper on how union membership helps narrow racial inequality for Black workers here.