January 20, 2015

E.J. Dionne had a very nice piece in the Washington Post last Thursday on how the U.S. tax code is less progressive than most reporting indicates. Dionne’s main point is that by focusing on federal taxes, many journalists miss out on state and local taxes, which tend to tax the poor at higher rates than the rich:

“It is thus a public service that the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) has issued a report showing that, at the state and local level, government is indeed engaged in redistribution — but it’s redistribution from the poor and the middle class to the wealthy.

“The institute found that in 2015 the poorest fifth of Americans will pay, on average, 10.9 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes and the middle fifth will pay 9.4 percent. But the top 1 percent will pay states and localities only 5.4 percent of their incomes in taxes.”

Dionne attributes the regressive nature of state and local taxes to the types of taxes that these areas tend to impose. As he notes, states and localities often rely heavily on sales and excise taxes; according to the ITEP report, both taxes are quite regressive. Property taxes are also regressive, though state-level income taxes tend to be progressive.

But there’s another way in which state and local taxes tend to be regressive: they contribute to inequality between states.

Think of a hypothetical country with two different regions. In Region 1, half of all income earners make $10,000 per year, and half make $30,000 per year. Region 2 has the same distribution of income—three-quarters of all income goes to those in the upper half of the income distribution—but has a substantially higher level of income. In Region 2, income earners in the bottom half of the distribution make $100,000 per year, and those in the top half make $300,000 per year.

In this scenario, both regions experience significant inequality. But most of the country’s inequality comes not from inequality within a given region but rather from inequality between the two regions. Average annual income in the first region is $20,000, but it’s a full $200,000 in the second. Even the highest income earners in the first region—those making $30,000 per year—make far less than the poorest members of Region 2, where nobody makes less than $100,000.

This is relevant to tax policy because poor regions have to pay much higher tax rates than wealthy regions for even basic services. For example, if Region 1 were to fund its local schools with a 50 percent tax on its citizens, it would raise $10,000 per taxpayer. If Region 2 were to fund its local schools with a 20 percent tax, it would raise $40,000 per taxpayer. This means that the people of Region 1 would pay a far higher tax rate than the people of Region 2, yet would still receive lower quality schools.

You can see this phenomenon in the United States. The U.S. Census Bureau found that, in 2011, just five states had higher levels of income inequality than the country as a whole. (Thirty-three had lower inequality, and twelve had levels of inequality roughly on par with the U.S.)

For a point of comparison, I decided to examine differences in tax policy between Indiana and Connecticut, the two states where I’ve spent most of my life.

Consistent with Dionne’s column, both states have regressive tax structures. (Information on Indiana can be found here; information on Connecticut can be found here.) In Indiana, those in the bottom fifth of the income distribution will pay 12.0 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes this year; those in the top 1 percent will pay just 5.2 percent. Connecticut’s tax code is more progressive than Indiana’s, but is still regressive overall: those in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution will pay 10.5 percent of their incomes in state and local taxes, but those in the top 1 percent will pay only 5.3 percent.

Yet there’s another big difference between the states: Connecticut has significantly higher per capita income than Indiana. In Indiana, those in the bottom fifth of the income distribution make less than $19,000 per year; in Connecticut, the threshold is $6,000 greater. In order make it into the top 1 percent in Indiana, you have to make $356,000 annually; in Connecticut, you have to make $1,331,000, nearly four times as much. According to the St. Louis Fed’s Geographical Economic Data, per capita personal income in Indiana was $38,812 in 2013; in Connecticut, it was $60,847. In 2013, Indiana would have needed to tax its residents at over 1.5 times the rate in Connecticut just to match Connecticut’s per capita revenue.

State and local taxes are regressive by design, but they’re also regressive by nature. Even if each individual state had a progressive tax code, one regressive element would remain: poorer states would have to tax their residents at far higher rates than richer states would.

So state and local taxes are characteristically regressive. And those regressive taxes have become a more prominent feature of the U.S. tax code over time:

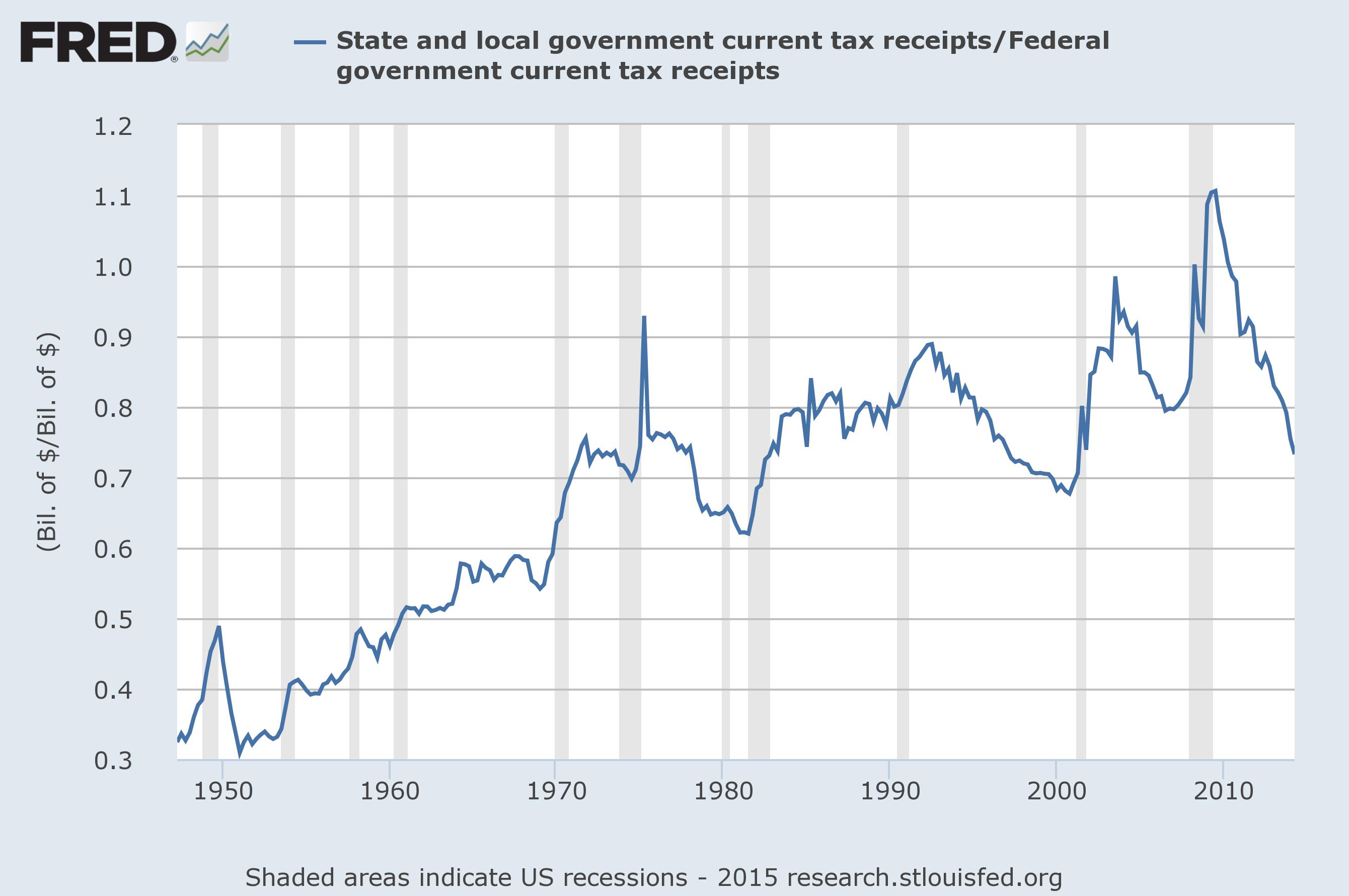

The above graph, courtesy of the St. Louis Federal Reserve, shows the ratio of state and local tax revenue to federal tax revenue. In an increasingly unequal society, tax policy could have become more progressive to offset the rise in market-based inequality. Instead, regressive state and local taxes came to play a larger role in the U.S. tax code, compounding rather than negating the rise in pretax inequality.

Not every aspect of economic policy should be federalized. But when assessing tax policy, it’s important to remember the differential resources across states and localities. If we want to ensure that government does not compound inequality through time, we should be trying to reverse the trend towards greater state and local taxation.