July 09, 2007

July 9, 2007, Testimony of Heather Boushey before the D.C. City Council

Thank you Chairperson Schwartz and members of the Workforce and Development and Government Operations Committee for allowing me to testify today on the need for the Paid Sick and Safe Days Act of 2007.

My name is Heather Boushey and I am a senior economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, a non-partisan think tank in Washington, DC. My area of expertise is the U.S. labor market, with an emphasis on the interconnections between labor, social policy, and work/life balance.

The Paid Sick and Safe Days Act of 2007 would provide workers the right to take paid time off when they or their immediate family members are ill, or need routine or preventative medical care. The bill would also cover parental leave and absences associated with domestic violence.

This bill, as it is currently formulated, would be a critical step forward for workers in the District of Columbia. When someone is ill, they need to be able to take sufficient time to get well. Having sick people show up at work, especially in sectors like retail, food service, and hospitality, only spreads disease and lowers productivity. But this bill does more than allow workers time off for their own illness; this bill recognizes that, unlike just a generation ago, most families do not have a stay-at-home parent that has the time to provide care to other family members when they become ill, or to attend a parent-teacher conference during school hours.

As a labor economist, I want to provide several findings as background for why this legislation is so important.

Women—and mothers—are in the labor force to stay. There’s no evidence that women—neither professional women nor the other 90-some percent of working mothers—are increasingly leaving the labor market to be full-time caretakers. In 2005, the last year for which we have data on mothers, among prime-age women (aged 25 to 45), 75 percent of women and 71 percent of mothers were in the labor force.

Most families simply cannot afford to have a full-time caretaker at home. Women work because their families need their income. The typical working wife brings home over a third of her family’s total income (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2005) and single mothers often do not receive child support and must support themselves. Many women also work because they need benefits for themselves and their families, such as health insurance coverage or retirement benefits. Most families can neither afford to have a stay-at-home-mother, nor a full-time nanny who can help families cope with fluctuating work schedules.

As a result, the overwhelming majority of children do not have a full-time caretaker at home and so families must find a way to create work/life balance. Two-thirds of families with children have all available parents at work: in 62 percent of married-couple families, both parents work, and in 71 percent single-mother families and 83 percent of single-father families, the parent works (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2006). Parents—mothers and fathers—now typically both work and provide care, and many workers also provide care for elderly parents.

Yet, many—if not most—U.S. workplaces continue to act as if their workers have a full-time spouse at home to provide care. Achieving work/life balance is not a problem for just a few U.S. workers but, rather, is the norm for the majority of the U.S. workforce. Workers across a multitude of demographic dimensions—age, race, ethnicity, marital status, income, educational attainment, and kind of job—face work/life issues. Yet, nearly two-thirds of workers report that they do not have paid sick days to cover their time if a family member is ill (Lovell 2004).

Providing paid sick days to every worker is a critical step forward in recognizing the realities of today’s labor market and how families can balance their work responsibilities and their care responsibilities.

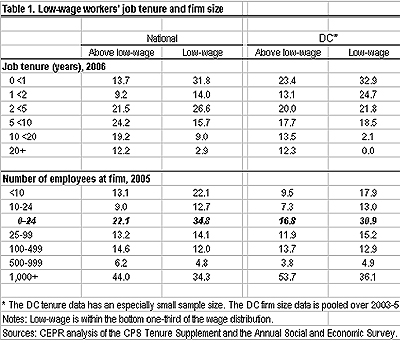

A key component of this legislation is that it applies to all workers equally. Access to paid sick days needs to be a labor standard that applies to everyone, like the minimum wage. By way of example, Table 1 shows the typical job tenure and size of firm for low-wage workers and higher-waged workers nationally and in the District of Columbia. Low-wage workers typically have shorter job tenure than higher-waged workers, and are concentrated in smaller firms.

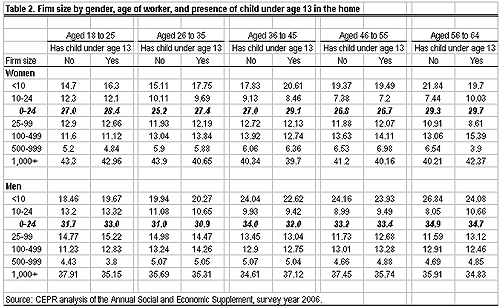

Table 2 breaks down the percentage of workers with children under age 13 at home, by age of worker and firm size for the nation (sample sizes are too small to do only for the District of Columbia). Across age groups, workers with children at home are slightly more likely to work in small firms, with around a third in firms with fewer than 25 people.

As drafted, this bill affords the right to paid sick and safe days to all workers, regardless of firm size or job tenure. This is a critical component of the bill and is essential to ensuring that those who can least afford to lose a day’s pay to illness or seeking protection from abuse are covered by the Paid Sick and Safe Days Act of 2007.

Heather Boushey is a Senior Economist at the Center for Economist and Policy Research.