This report originally appeared as a chapter in the book The Contributions of Health Care Management to Grand Health Care Challenges. The original text can be found here.

The long-term financial stability of hospital systems represents a ‘grand challenge’ in healthcare. New ownership forms, such as private equity (PE), promise to achieve better financial performance than non-profit or for-profit systems. In this study, we compare two systems with many similarities, but radically different ownership structures, missions, governance, and merger and acquisition (M&A) strategies. Both were non-profit, religious systems serving low-income communities – Montefiore Health System and Caritas Christi Health Care.

Montefiore’s M&A strategy was to invest in local hospitals and create an integrated regional system, increasing revenues by adding primary doctors and community hospitals as feeders into the system and achieving efficiencies through effective resource allocation across specialized units. Slow and steady timing of acquisitions allowed for organizational learning and balancing of debt and equity. By 2019, it owned 11 hospitals with 40,000 employees and had strong positive financials and low reliance on debt.

By contrast, in 2010, PE firm Cerberus Capital bought out Caritas (renamed Steward Healthcare System), and took control of the Board of Directors, who set the system’s strategic direction. Cerberus used Steward as a platform for a massive debt driven acquisition strategy. In 2016, it sold off most of its hospitals’ property for $1.25 billion, leaving hospitals saddled with long-term inflated leases; paid itself almost $500 million in dividends; and used the rest for leveraged buyouts of 27 hospitals in 9 states in 3 years. The rapid, scattershot M&A strategy was designed to create a large corporation that could be sold off in five years for financial gain — not for healthcare integration. Its debt load exploded, and by 2019, its financials were deeply in the red. Its Massachusetts hospitals were the worst financial performers of any system in the state. Cerberus exited Steward in 2020 in a deal that left its physicians, the new owners, holding the debt.

Journal citation: La France, Aimee, Rosemary Batt, and Eileen Appelbaum. 2021. “Hospital Ownership and Financial Stability: A Matched Case Comparison of a Non-Profit Health System and a Private Equity Owned Health System.” In Jennifer Hefner and Ingrid Nembhard, eds., The Contributions of Health Care Management to Grand Health Care Challenges. Volume 20, Advances in Health Care Management, pp 173-226. Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing1.

Concern over hospital financial stability has grown substantially in the last decade. The Great Recession of 2008 dug deeply into hospital finances, competition to attract patients increased, and the federal government reduced reimbursement rates while promoting preventative care through population health management (PHM) – which shifts financial risk to hospitals. In 2019, before the Covid-19 pandemic hit, almost 900 U.S. hospitals were in immediate risk of closure and 30 hospitals closed. By 2020, hospitals lost an estimated $323 billion in revenue, saved largely by government rescue packages — and 47 closed (Ellison, 2020a; 2021). A well-known industry ‘financial distress index’ estimated that the level of distress was five times higher in 2020 compared to 2010 (Bloomberg Law, 2020).

The long-term financial stability of hospital systems represents a ‘grand challenge’ in the healthcare sector that will continue post-pandemic. In this context, scholars, policy makers, and practitioners have shown increasing interest in new ownership forms as a financial solution – including for-profit and private-equity owned systems. Even non-profits have expanded their investments in for-profit subsidiaries to support their healthcare operations. Without stability, hospital systems lack the resources to serve patients in need or to invest in new technologies and processes that reduce costs and improve patient care. Arguably, for-profit ownership provides a solution because shareholders exert more pressure to increase revenues and decrease costs in ways that non-profit system owners do not. Evidence exists that on average for-profit systems are more financially efficient than non-profit systems (Holt, Clark, DelliFraine, & Brannon, 2011).

More recently, private equity (PE) firms argue that they can help solve healthcare’s financial crisis by bringing in much needed financial expertise to drive management efficiencies – more so than for-profit chains. That is because, compared to a typical for-profit corporation, ownership is concentrated in one private investment fund, which acts as an activist shareholder with greater incentives to adopt radical strategies to maximize revenues and minimize costs. PE firms also claim they drive efficiencies through mergers and acquisitions (M&As) – a financial strategy designed to increase revenues, drive down costs through economies of scale, and expand opportunities for PHM. While M&As have grown among all healthcare systems, the number of PE-driven M&As has grown at four times the rate of non-PE M&As. By 2019, PE M&A deals in healthcare represented 45 percent of all M&As in the sector, substantially higher than the proportion of providers that PE actually owns (PitchBook data, 2019). This prevalence of PE in M&A deals is related to the fact that PE ownership in healthcare has expanded dramatically – growing from less than $5 billion annually in 2000 to $100 billion in 2018 – a 20-fold increase (Appelbaum & Batt, 2020: 14).

Critics argue, however, that the PE model does not fit healthcare organizations if its focus on financial efficiency undermines the ability to provide high quality care. Whether both may be achieved simultaneously is contested. Some medical professionals also worry that under PE ownership they will lose their professional autonomy and control over decision-making (Gondi & Song, 2019).

In this paper, we explore the importance of different hospital system ownership structures by comparing a non-profit system and a PE owned one. We draw on the conceptual framework developed by Holt and colleagues (2011) that identifies the key organizational factors that shape hospital financial performance. While we do not have the data to present a causal argument, our detailed case studies illustrate how and why Holt and colleagues’ theoretical model has merit and deserves further research. Our analysis contributes to the literature by providing credible evidence of how and why different ownership forms matter, and how they are linked to other important system features: organizational mission, governance, and integration (M&A) strategies. We show how these linkages play out in the real world, and we compare their financial and patient care outcomes where data is available.

Our matched case comparison draws on two hospital systems with many similarities, but radically different ownership structures. Until 2010, both were non-profit, religious systems serving low-income communities – Montefiore Health System in the Bronx, New York, and Caritas Christi Health Care in the communities surrounding Boston, Massachusetts. Montefiore has continued as a non-profit system, while also expanding its for-profit complementary operations. By contrast, in 2010 the Archdiocese of Boston chose to turn Caritas into a for-profit system and sell it to a PE firm, Cerberus Capital Management. Both systems engaged in vertical and horizontal integration strategies (M&As) to expand their population base and revenues; but their approaches to organizational mission, governance, and M&A strategies were radically different, as were their financial outcomes. Our multi-year study traces these systems between 2010 and 2019 – drawing on secondary sources, local news sources, the hospitals’ own websites and public announcements, publicly available data on hospital metrics, field research, and 25 interviews conducted with hospital managers, union leaders, and external industry experts. We provide publicly available financial outcome data where available, however, PE owned corporations are private and generally do not release financial data. We do present comparable patient care data from the Pioneer ACO program when both systems participated in that program.

To preview our findings, we show that Montefiore maintained a social mission of serving low-income communities and a governance structure of primarily medical professionals on its board. They prioritized using an M&A strategy to expand the healthcare system in a contiguous geographical area to create an integrated regional system. The strategy allowed it to increase revenues by integrating more patients into its system through primary care doctors and community hospitals as feeders into the system; simultaneously it achieved system efficiencies through effective resource allocation across specialized units. Patients from outlying communities also benefited from access to more sophisticated healthcare in Montefiore’s Medical Center. Slow and steady timing of acquisitions allowed for organizational learning over time and balancing of debt and equity. It also complemented its healthcare operating income with for-profit subsidiary income. Montefiore was a top quality performer in the Accountable Care Act’s (ACA) Pioneer Program. By 2019, it owned 11 hospitals with 40,000 employees in one region, and had strong positive financials — net assets, net income, operating margins, and equity financing ratio (low reliance on debt financing).

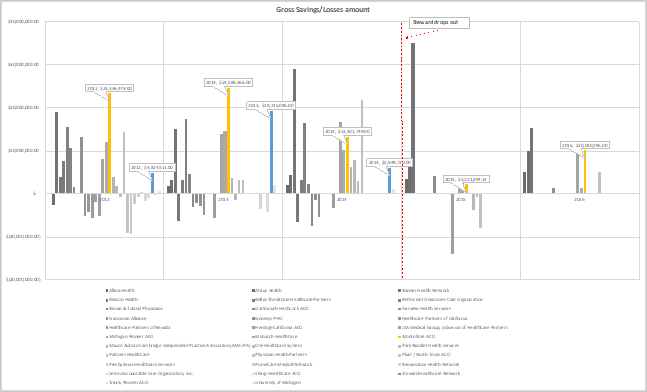

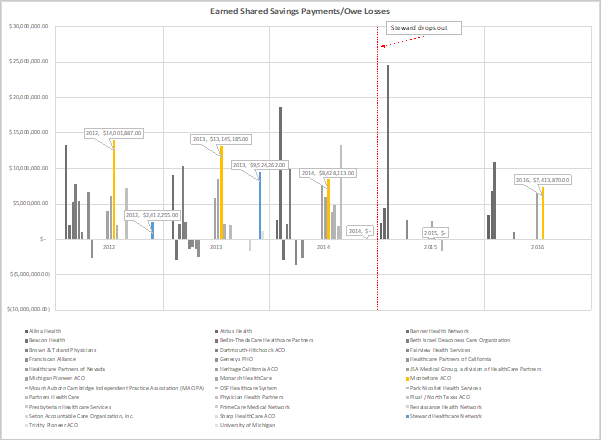

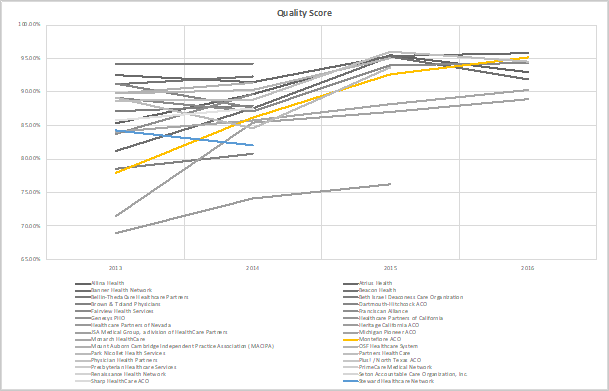

By contrast, after Cerberus Capital bought out Caritas and christened it Steward Healthcare in 2010, its acquisition strategy became debt driven. It was a top performer in the ACA’s Pioneer Program in 2012, but thereafter its scores declined somewhat and it dropped out. And after 2015 when it was freed from the regulatory oversight of the Massachusetts Attorney General (AG) (a condition of its conversion from a non-profit to for-profit corporation), it sold off the property of most of its hospitals for $1.25 billion, paid itself large dividends, and launched a massive leveraged buyout campaign — acquiring 27 hospitals in 9 states in less than 3 years. The rapid, scattered M&A strategy was designed to create a large corporation that could be sold off in five years for financial gain — not for healthcare integration. Its debt load exploded, and by 2019, the financial ratings of its Massachusetts hospitals were the lowest of any system in the state. Its Massachusetts healthcare system financials – net assets, net income, operating margins, and equity financing ratio — were deeply in the red. Its hospitals remained financially fragile, paying inflated rent on long-term leases. One of its former hospital’s property was turned into a 465-unit apartment building complex after the closure of its Emergency Department. And in a desperate move in 2020, Cerberus threatened closure of one of its Pennsylvania hospitals unless it received Covid-related government bailouts (which it did). Cerberus exited Steward in 2020 in a deal that left its physicians, the new owners, holding the debt.

A theoretical framework for the relationship between organizational factors and financial performance was developed by Holt and colleagues (2011) based on a review of hundreds of research papers on the topic published between 1984 and 2010. This research covered the period in which hospitals faced increasing cost pressures due to a series of reductions in federal funding beginning with the shift in 1983 from a cost-plus model to a prospective one based on Diagnostic Related Groups (DRGs) (Mayes and Berenson 2006). The interdisciplinary framework integrates theories from management and organization studies and identifies five categories of factors that prior studies have found important: ownership, governance and organizational mission, integration, management strategy, and quality. Our study focuses on the first three factors.

Ownership

A considerable number of studies have focused on whether and why for-profit versus non-profit ownership leads to different financial outcomes in hospitals. At a general level, economic theory posits that market competition and the profit motive make for-profit organizations more efficient than non-profit ones. At a more specific level, three theoretical frameworks support the idea that for-profit status should lead to better results. Agency theory posits that managers, left to their own preferences, will prioritize their own interests or other goals rather than financial goals, which may be harder to realize or may not be relevant to their own interests. In order to curb this managerial opportunism, owners of capital need more direct control over managers to align their activities with the financial goals of the owners (Jenson & Meckling, 1976). A parallel argument that for-profit status brings better financial performance draws on public choice theory, which posits that politicians may interfere with public or non-profit institutions for their own political gain (Curevo & Villalonga, 2000). That is, political opportunism may lead to poor financial performance.

Institutional theory likewise would suggest that for-profit hospitals outperform non-profits due to institutional inertia or path dependence. Institutional scholars define path dependence as a process in which early historical events trigger a subsequent sequence that ‘follows a relatively deterministic pattern,’ or ‘inertia,’ with stable reproduction of the institutional arrangement over time (Mahoney, 2000: 535). Most U.S. hospitals are non-profit systems with deep institutional legacies of missions to serve their communities’ healthcare needs regardless of cost. This is especially true of hospitals founded by religious institutions, as carefully articulated in the ethnography of Santa Rosa Memorial Hospital, a Catholic hospital where workers resisted unionization for a decade because they believed the union would undermine the hospital’s Catholic patient care mission, which they were committed to (Reich, 2012). A similar story unfolded in nursing home campaigns in Pennsylvania (Lopez, 2004).

Empirical studies have mostly found that financial performance is, indeed, stronger in for-profit compared to non-profit hospitals – both in cross-sectional comparisons and in longitudinal studies of non-profit hospitals that convert to for-profit status (Holt et al., 2011: 28-29, Table 2). That general finding, however, may be moderated by other organizational factors, such as a hospital’s organizational mission. Thus, for-profit hospitals that maintain a strong patient care mission may deviate from the general pattern; likewise for non-profit hospitals that behave like for-profit ones and prioritize financial performance. Detailed case studies provide the opportunity to examine this type of conditionality.

Studies of PE owned hospitals, however, are thin. Agency theory would nonetheless suggest that PE ownership should provide even better financial performance than other for-profit models because PE represents a more concentrated shareholder model that further reduces agency problems of misalignment between owners and managers, pushing managers to cut costs and improve profits wherever possible.

Yet the PE model has particular features that also create higher risks for the organizations it buys. To understand these risks, a short review of how the PE model works is needed. First, PE firms set up investment funds, led by a team referred to as the general partner (GP), and recruit investors (or limited partners, LPs) to make commitments to the fund, typically for a period of 10 years. The LPs also pay a 2 percent annual management fee to the GPs, who take 20 percent of the returns over a given hurdle rate of return. LPs invest with the expectation that the fund will yield ‘outsized’ returns (higher than the stock market). Given the illiquid nature of the LPs’ investment, returns should be about three percentage points above the stock market. This promise in itself creates pressure for PE funds to deliver higher returns than those of the typical for-profit corporation.

Second, PE makes heavy use of debt to buyout companies – leading to a capital structure for the acquired company that is typically 70 percent debt and 30 percent equity – compared to the capital structure of the typical publicly traded for-profit corporation, which is the reverse. The debt is loaded on the portfolio company (in this case the hospital system), which must service the debt by maximizing cash flow. Again, this debt structure puts pressure on the PE-owned health system to cut costs to service the debt, reducing resources available for investing in workforce skills, technology, or other processes to improve efficiencies or patient care.

Third, the time horizon for PE firms to exit their investments is typically 3- to 5-years (Appelbaum & Batt, 2014). This intensifies the pressure on PE owned hospitals to cut costs and increase revenues quickly. Once a PE firm acquires a company, it puts its partners on the board of directors, hires or fires the CEO, and develops a strategic plan to ensure that the PE fund extracts as much cash flow from the company as is needed to service debt and reward investors. This can be done through operational improvements (overhauling poor management, improving accounting systems, investing in updated technology) or through financial engineering (cutting costs, layoffs, selling assets, requiring the company to issue more debt and use the proceeds to pay dividends). The PE firm also typically requires the portfolio company to sign a Management Services Agreement (MSA) that includes monitoring and advisory fees paid directly to the PE firm.

In sum, it is an empirical question as to whether, following agency theory, PE aligns the financial strategies of managers with the profit maximizing goals of shareholders in ways that improve hospital financial performance; or whether PE’s strategies for maximizing returns in a short time frame lead to excessive wealth extraction that undermines financial stability. The few empirical studies that have been done show that PE owned companies have considerably higher financial distress, as evidenced in higher bankruptcy rates, than do comparable publicly traded companies (Strömberg, 2008; Appelbaum & Batt, 2014, chapter 4; Appelbaum & Batt, 2018; Ayash & Bastad, 2019; Baker, Corser, & Vitulli, 2019).

Few studies have examined how PE ownership affects healthcare providers, but one literature review developed theoretical propositions that financial performance in PE-owned nursing homes should be better than in for-profit or non-profit homes, while the quality of care should be worse (Pradhan & Weech-Maldonado, 2011). The review included two relevant studies, one that found that RN staffing levels were significantly lower in PE-owned nursing homes (indicating greater cost cutting strategies) (Stevenson & Grabowski, 2008) and another that found that deficiencies, a measure sensitive to RN staffing, were higher (Pradhan, 2010). A recent study found that PE owned nursing homes had 10 percent higher Medicare patient mortality rates, equivalent to 20,150 lives lost to PE ownership over a 12-year period. They also found lower levels of nursing staff, lower compliance with standards, and a shift in operating costs post-acquisition to non-patient care items that included monitoring fees, interest, and lease payments (Gupta, Howell, Yannelis, & Gupta, 2021).

Mission and Governance

Hospital mission and governance are likely to be closely aligned with ownership to the extent that owners establish the mission and choose, or have substantial control over, the board of directors. The board of directors charts the strategic direction of the organization. Consistent with agency theory, external owners or shareholders are likely to select board members who are independent from the CEO or top management, and therefore better positioned to monitor their behavior and ensure that their decisions support better financial performance.

Beyond the level of board independence is the question of member composition and processes. This has important implications for financial performance in two ways. First, board members provide a link to the external environment, both in terms of access to resources and to political support to minimize uncertainty, as resource dependency theory would argue (Pfeffer & Salancik 2003; Kane, Clark, & Rivenson, 2009). Second, they provide expertise. For better financial performance, board members should bring to the table the expertise that ‘fits’ the organization’s needs: financial as well as operational or industry expertise, as posited in strategic management theory. In the context of hospitals, physician board members may provide valuable insights on best practices in patient care delivery and services delivery. Several empirical studies have found that physician membership on the board improves financial performance, although most of these studies date to the 1990s (Holt et al., 2011, Table 3). Arguably, however, physician participation on boards of directors should be more important in the current environment in which hospital system revenues depend importantly on the effective integration of physician practices into the network.

Integration (M&A) Strategies

In the last two decades, and particularly since 2010, vertical and horizontal integration have become critical for hospitals to achieve better financial and patient care outcomes. Vertical integration includes the incorporation of physicians’ practices and health plans into hospital systems. Horizontal integration includes the expansion of hospital networks via mergers and acquisitions, alliances, or joint ventures – including the mergers of hospitals as well as the incorporation of outpatient facilities into the network.

Vertical integration strategies (hospitals, insurance companies, physician practices, etc.) are central to hospitals’ financial performance, especially in the current period as they shift to population health management or value-based care. Hospitals that own insurance companies have access to claims data that provides the basis for identifying clusters of chronic diseases that may be managed through lower-cost population health management practices. The integration of physician practices into hospital systems increases patient referrals and, in turn, revenue generation.

Horizontal mergers benefit hospitals in several ways. They reduce costs through economies of scale and increase revenues through access to new markets or a broader population pool. They position hospitals to have greater bargaining power vis-a-vis suppliers and payers. In keeping with resource dependency theory, they allow hospital systems to gain control over more resources, for example, by assisting small hospitals to gain better access to capital or reduce the costs of capital (Carroll, Smith, & Wheeler, 2011) or by gaining access to a patient population with a stronger commercial payer base. And consistent with strategic management theory, M&As allow hospital systems to diversify service offerings – for example, by incorporating hospitals with different types of specialties, or different ‘value-added’ services, into their networks.

Hospitals have gone through successive waves of M&As: in the 1980s in response to the introduction of DRGs, and again in the 1990s, the 2000s, and since 2010 (Appelbaum & Batt, 2017). For-profit hospital chains grew dramatically from a very low share of hospitals in the 1980s to about 10.5 percent of all hospitals by 2000. Non-profit hospitals went through a wave of M&As in 1994 to 1997, peaking in 1997 at just under 200, before falling off (Ettinger & Berenbaum, 1996; Irving Levin Associates, Inc., 2013). A second M&A wave of hospitals took off between 2004 and 2007 in response to access to low-cost debt and reforms to the Balanced Budget Act. This time, PE firms engaged in large leveraged buyouts, due in part to the recession proof nature of healthcare and the stable cash flow of government subsidies. A third wave of M&As followed the passage of the ACA in 2010, spurred by the increase in the number of insured persons by 20 million. Cuts in Medicaid and Medicare reimbursement rates and the shift from the fee-for-service (FFS) payment model to fee-for-value (FFV) also encouraged M&As, and PE firms again rushed into this market anticipating lucrative returns. By February 2011, eight of the largest twelve for-profit chains were owned by PE (Appelbaum & Batt, 2020: 25-26; Table 3.1).

In recent years, non-profits have adopted the growth strategies of for-profits in order to survive, with roughly 75 percent of deals involving a non-profit as the acquirer (Kaufman Hall, 2019). Also on the rise are mega mergers, in which two hospital systems with revenues of $1 billion or more merge to form large regional systems, as reflected in the increasing average value of transactions per year. In 2018, 51 percent of deals were valued at less than $100 million, yet the average transaction size was $409 million (Kaufman Hall, 2019).

PE firms have used both vertical and horizontal integration strategies to create national for-profit healthcare systems that include hospitals, outpatient care centers, physicians’ practices, and other specialized units. They use a well-developed ‘buy and build’ strategy in which they establish a ‘platform’ by buying out one enterprise and then adding on and rolling up a series of similar enterprises (Appelbaum & Batt, 2020: 11). The strategy allows PE firms to operate below the radar of anti-trust regulators because any one acquisition is often too small to fall under their jurisdiction, but overall, the strategy helps PE achieve economies of scale and market power at the local, regional, or national level. The strategy also dilutes the overall purchase price of the expanded company and facilitates a profitable exit.

Research Methodology

The research strategy for this study was to undertake a matched case comparison of two hospital systems that have similar organizational characteristics and have actively engaged in M&As but have radically different ownership structures: a not-for-profit system and a PE owned system. We chose the Montefiore Health System and Steward Health Care System (formerly Caritas Christi Health Care). Both were founded as religious institutions – non-profit hospitals with a strong social mission to serve their disproportionately sick and elderly communities. Montefiore was established by Jewish philanthropists to serve the lower income Bronx community, while Caritas was established by the archdiocese of Boston to serve surrounding low-income communities.

| Montefiore Health System | Steward Health Care System (formerly Caritas Christi Health Care) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Year Founded | 1884 | 1985/2010* |

| Founder | Jewish Philanthropists | Archdiocese of Boston/Dr. Ralph de la Torre* |

| Current CEO | Dr. Philip Ozuah | Dr. Ralph de la Torre |

| Status | Non-profit | Former non-profit converted to a for-profit |

| Headquarters | Bronx, NY | Boston, MA 2010 – 2018 Dallas, TX 2018 – present |

| *While Caritas was founded in 1984 by the Archdiocese of Boston, when it sold to Cerberus in 2010, it was brought under the newly created healthcare system Steward with Ralph de la Torre as the founder Sources: 1 – Montefiore State Budget Testimony 2 – Steward Company Overview |

||

Both systems historically faced steep financial pressures as they served disproportionately high Medicaid and Medicare populations (although the population of the Bronx had more than twice the poverty rates and number of uninsured individuals under 65, and substantially higher Medicaid eligible individuals). Early on, the leadership at both hospital systems understood the necessity of shifting to a population health management model – especially after the passage of the ACA and the financial pressures it imposed. Population health management is designed to identify the health problems in a given population and manage it proactively to improve care quality and reduce costly hospital visits.

| County Demographics (2018): Boston area (Steward) versus the Bronx (Montefiore) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| County | Population Size | Uninsured below 65 (%) | Median Household Income | Persons in poverty (%) | Eligible for Medicaid (%) |

| Suffolk | 803,907 | 4.40% | $64,582.00 | 17.50% | 41.11% |

| Brockton | 95,708 | 4.00% | $55,140.00 | 15.60% | N/A |

| Norfolk | 706,775 | 2.40% | $99,511.00 | 6.50% | 20.65% |

| Bristol | 565,217 | 3.70% | $66,147.00 | 10.80% | 32.05% |

| Essex | 789,034 | 3.80% | $75,878.00 | 10.70% | 25.31% |

| Boston area (Steward) Sum/Average | 2,960,641 | 3.66% | $72,251.60 | 12.22% | 29.78% |

| Bronx (Montefiore) Sum/Average | 1,418,207 | 8.70% | $38,085.00 | 27.30% | 43.06% |

| Sources: 1 – U.S. Census Bureau 2 – Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services” |

|||||

To implement this strategy, the leaders at both systems pursued vertical and horizontal integration via M&As, sought to develop a strong network of physicians, undertook capitated contracts with insurance companies, and used advanced technology and data analysis for care coordination. By 2012, both Montefiore and Steward were among the 32 hospitals selected by the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) to participate as Pioneer Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs). Steward achieved this status at the same time as Montefiore, even though Montefiore had considerably more experience with this model. To be eligible for the Pioneer ACO Program, participants must fall under one of the five categories the CMS outlines as a provider or supplier of services. They also must have at least 50% of their primary care providers meet requirements for the meaningful use of EHRs to receive payments and have a minimum of 15,000 aligned beneficiaries (unless located in a rural area where the minimum is 5,000) (CMS, n.d.-b).

Both hospitals were also largely unionized and paid high relative wages and benefits, so that differences in labor costs did not differentiate them, nor did differences in union-management relations, which were generally positive in both systems. Local 1199, Healthcare Division of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and New York State (NYS) Nurses Association represented Montefiore workers; and the same division of SEIU and Massachusetts Nurses Association represented Caritas (Steward) workers.2

The primary difference between the two systems is that Montefiore has continued to be a non-profit institution while Steward became PE owned in 2010. This difference in ownership structure is our primary explanatory variable regarding why the decision makers in the two systems adopted radically different governance and integration strategies. Their financial and patient care outcomes were also radically different. We also take into account in our analysis the fact that Montefiore, as a medical teaching hospital had higher Medicaid reimbursement rates and care quality scores; but this difference does not explain the processes and outcomes we observe.

We conducted a multi-year study of the two systems and traced their strategies and development between 2010 and 2020. Our research draws on secondary sources, local news sources, the hospitals’ own websites and public announcements, publicly available data on hospital financial and healthcare metrics, field research, and 25 interviews conducted with hospital managers with different types of expertise (finance, HR, nursing), union leaders, and external legal and healthcare industry experts. The opportunity to interview people with a wide range of responsibilities and perspectives helped us understand how the healthcare systems were responding to external pressures. We conducted initial field research in the 2012–2014 period and follow-up research in the 2018-2020 period. We also examined publicly available performance data from the CMS on Steward and Montefiore during their involvement in the Pioneer ACO program.

In our case analyses, we present brief historical backgrounds of each hospital system as well as their ownership, governance (board membership), and integration strategies. We outline a timeline of their expansion efforts, including which healthcare systems they acquired, when they acquired them, where those systems are located, and the reported reason for the acquisition. In addition, we discuss the outcomes of the hospitals’ expansion strategies: their financial stability and growth, their reported healthcare metrics where available, the public sentiment regarding their expansion efforts, and the effects on labor relations.

Montefiore Health System is a nationally recognized hospital system operating in the Bronx – a county of 1.4 million people and one of the poorest in the country – with 27.3 percent of people (44 percent of children) living below the poverty level. Fifty percent of the population is Hispanic and over 30 percent is Black. It ranks last (62nd) of all NY state counties on virtually all social, economic, and health indicators, with particularly high rates of chronic disease and poverty-related health problems (NYS County Health Rankings, 2014). Eighty-four percent people are covered by Medicare or Medicaid, and 8.9 percent are uninsured (United States Census Bureau, n.d.).

Ownership, Mission, and Governance

New York’s Jewish philanthropic community founded Montefiore in 1884 as a non-profit Home for Chronic Invalids not served by other healthcare providers. This social mission has a deep and on-going institutional legacy. Its core hospital in the Bronx was established in 1912. It was among the first in the country to establish a Department of Social Work (1905), Department of Home Health Care (1930s), Department of Social Medicine (1950), and a residency program in Social Medicine (1970) (Montefiore Medical Center, n.d.).

The leadership at Montefiore has consisted of medical professionals who rose through the ranks and used their medical expertise to decide where and how to expand services. Exemplifying this tradition is Dr. Steven Safyer, who between 1998 and 2008 rose in leadership positions to become president and CEO from 2008 to 2019 (Montefiore Medical Center, 2019). Safyer led many of Montefiore’s innovative strategies – including value-based pay systems and the hospital’s programs for the incarcerated at Rikers Island as well as combating New York City’s HIV and tuberculosis epidemics. From 2008 on, he led Montefiore’s strategic geographic expansion to include hospitals throughout the Hudson Valley and Westchester County (Meyer, 2019).

Montefiore’s board of directors has historically included a disproportionate number of medical professionals. The current board includes eleven members: five with MDs, three with a finance background, one with a legal background, and two with social work backgrounds serving as patient care representatives (See Table 3). This board is responsible for making the strategic decisions that guide the growth and development of the hospital system.

| Montefiore | Steward | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Title | Name | Title |

| Philip Ozuah, MD | Voting Member and Chairman, Montefiore ACO; Executive Vice President, Chief Operating Officer, Montefiore Medical Center (Note: Recently promoted to CEO) | Ralph De La Torre, MD | Founder, Chairman and CEO |

| Joel Perlman, CPA | Voting Member and President, Montefiore ACO; Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer of Montefiore | W. Brett Ingersoll | Co-Head of Private Equity and is a member of the Investment Committee at Cerberus Capital Management, L.P. |

| Christopher Panczner, JD | Voting Member and General Counsel, Montefiore ACO; Sr. VP and General Counsel, Montefiore Medical Center | Lisa Ann Gray, Esq. | General Counsel of Cerberus Operations Advisory Company, LLC and a member of its executive team |

| Diane Aparisio, MSW | Voting Member and Patient Representative; Geriatric Research Consultant | James J. Karam | President and founder of First Bristol Corp., a developer of retail shopping centers, office buildings and hotels throughout southern New England; Chairman of the Board of Governors of Caritas Christi until its sale |

| Manash Dasgupta, MD | Voting Member; Nephrologist; Nephrology, PLLC, Yonkers, New York | James T. Lenehan | Senior Operations advisor to Cerberus Capital Management, LP. Prior to Cerberus, he was Vice Chairman and President of Johnson & Johnson |

| Mario Garcia, MD | Voting Member; Chief of Cardiology, Dept. of Medicine, Montefiore Med. Center; Co-Director, Ctr for Heart and Vascular Care, Albert Einstein College of Medicine | Chan Glabato | Chief Executive Officer of Cerberus Operations and Advisory Company, LLC. |

| Laurie Jacobs, MD | Voting Member; Vice Chairman of Clinical and Educational Programs, Department of Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center; Director, Jack and Pearl Resnick Gerontology Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine | Michael Palmer | Senior Vice President in the Private Equity Group of Cerberus Capital Management, L.P. |

| Patrick Murphy, CPA | Voting Member; Chief Financial Officer, The Greater Hudson Valley Family Health Center, Inc., Cornwall, New York | ||

| Andrew Racine, MD, Ph.D. | Voting Member; Chief Medical Officer, Montefiore ACO; Sr. VP and Chief Medical Officer, Montefiore Medical Center | ||

| Stephen Rosenthal, MBA, MS | Voting Member and Chief Operating Officer, Montefiore ACO; President and Chief Operating Officer, CMO, Montefiore Care Management | ||

| Karl Stricker | Voting Member; Patient Representative | ||

Source:https://www.montefiore.org/documents/aco/montefiore_board_of_directors_aco_website.pdf, https://www.steward.org/about/leadership

Integration Strategies: A Coherent Regional Healthcare Model

Given Montefiore’s social mission and commitment to the region’s healthcare, its M&A strategy has focused on regional integration of payers and providers. Vertical integration began in the 1990s and horizontal integration in the late 2000s. Both have contributed to a regionally integrated and coherent system of healthcare delivery that takes advantage of scale economies, coordination across specialized units, and on-going innovation.

Vertical integration: Montefiore’s vertical integration strategy emerged in the 1990s in response to financial crisis and its high dependence on Medicaid and Medicare, which pay lower reimbursement rates than do commercial payers. The hospital system could not survive as a transactional provider based on fee-for-services, so it began shifting to a health maintenance organization (HMO); and HMO success depends on vertical integration of payers and physicians. The financial logic of HMOs is that they can reduce costs through preventative care that addresses the costliest diseases (such as diabetes) and prevents costly emergency room or inpatient services. HMOs are the precursors to the population health management of today. Both require a shift from fee-for-service to a capitated payment system. The hospital negotiates contracts with insurance companies in which the provider receives a fixed or capitated amount to provide all health care services to the insured member (the insurance company typically keeps about 10 percent of the premium). The provider has incentives to adopt cost-effective innovations and preventative care.

On the payer side, Montefiore created a wholly owned subsidiary in 1996 (the Care Management Company, CMO), which works with insurance providers (Aetna, US Healthcare, Blue Cross/Blue Shield, United Healthcare, etc.) to take over most of the functions of the health plan (paying claims, authorizing services, etc.). As of 2012, contracts covered 150,000 people (one-third of the patients served by the Montefiore System) and generated $750 million in annual revenues (Lazes, Katz, Figueroa, & Karpur, 2012: 154).

On the provider side, Montefiore succeeded in gaining the commitment of physicians by starting to employ them directly because they could not survive in the Bronx as independent providers. Building on this base, it established the Montefiore Independent Practice Association (IPA) in 1996, which brings together hospital-based and independent doctors affiliated with Montefiore. It created a similar one for behavioral health. These provider organizations contract with the insurance agencies, but the financial transactions flow through Montefiore’s CMO (Lazes et al., 2012: 154-5). As of 2011, the IPA included 2,400 physicians, including 1,600 working at Montefiore’s four hospitals and its roughly 100 primary and outpatient specialty offices and 800 community-based, private-practice doctors (AHRQ ND).

Critical to the commitment of physicians to the system is how they are treated. Montefiore makes no distinction between employed and independent doctors in the IPA but has an “open participative architecture.” It creates financial alignment by providing the same incentives for both employed and voluntary physicians through a system of performance metrics and a type of profit sharing. Money left over at end of year is split with physicians and the hospital community. More recently, Montefiore established a Medical Group Network with 350 physicians and other professionals based in 22 locations to manage ‘patient-centered medical homes.’

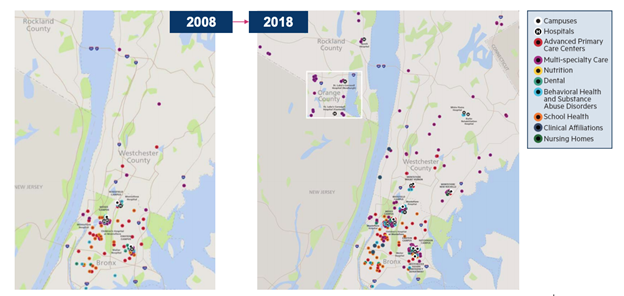

Horizontal integration: Following the 2008 recession, Montefiore began a substantial regional acquisition phase to expand the population of patients and its revenue base. Its primary strategy was to expand its geographic footprint into contiguous areas, and by 2019, it had acquired 16 hospital facilities from 12 healthcare systems. Its strategy also was to expand the network of ambulatory or outpatient clinics that provide better access to residents in community-based settings and serve as feeders to the major hospitals for more acute care. The regional location strategy is shown in Figure 1. Montefiore began by acquiring hospitals in the Bronx before moving out into the lower Hudson Valley, White Plains, New Rochelle, and Westchester.

Figure 1: Montefiore’s Regional Acquisition Strategy, 2008-2018

The acquisitions varied in their strategic value to Montefiore. The first three acquisitions were of nearby systems facing bankruptcy. Their acquisition (at a fraction of the value of their physical assets) allowed Montefiore to expand capacity in the Bronx and nearby communities. Montefiore also invested in them and undertook expansions that created hundreds of jobs in these communities. Additionally, under value-based care, Montefiore could encourage patients to use these lower cost facilities to reduce costs (Commins, 2013). An example is Our Lady of Mercy Medical Center (OLM) (with 369 beds, 2,500 employees, and over 500 physicians, Montefiore Medical Center, 2008) – now Wakefield campus. It went bankrupt in 2007 with $91.2 million in assets and $151.5 million in liabilities; the deal was worth $33.5 million (Montefiore Medical Center, 2008; Kappstatter, 2019; PitchBook, n.d.-b). After merger, Wakefield’s patient volume increased, efficiencies improved, and jobs were preserved (Merger Watch, 2014). Two other systems saved out of bankruptcy, with similar stories and outcomes, were the Westchester Square Medical Center (Commins, 2013; PitchBook, n.d.-c) and the Sound Shore Health System (Cision, 2013; Becker’s Hospital Review, 2013; Montefiore Medical Center, 2013a; Montefiore Medical Center, 2013b)).

These three acquisitions led the way for Montefiore to expand from the Bronx into the contiguous lower Hudson Valley – Westchester, New Rochelle, White Plains, Yonkers, and Nyack. Montefiore took advantage of New York State’s delivery system reform incentive payment program, or DSRIP, in 2014. DSRIP provides considerable funding to promote system reform and change the way Medicaid beneficiaries receive care, with a specific goal to reduce hospital readmissions by 25 percent over five years. To receive funding, providers are required to meet a specific set of performance metrics focused on system redesign, infrastructure development, clinical and population health improvements (Evans, 2015; Gates, Rudowitz, & Guyer, 2014; NYS Department of Health, n.d.).

Between 2014 and 2018, Montefiore completed nine more acquisitions or partnerships, with “building a regional healthcare delivery system” repeatedly cited as the primary reason (See White Plains Hospital, 2015; Becker’s Hospital Review, 2014; Evans, 2015). Hospitals acquired by Montefiore benefit from the greater array of services and exposure to Montefiore’s broad physician network as well as Montefiore’s assistance in executing managed care and population health management plans. According to the interim CEO of St. Luke’s Cornwall, Montefiore has “… really, really given us a great deal of sweat equity, their physicians are becoming our physicians, they’re working with us as they really advance our care management and our population health strategy. Now we’re part of something bigger, and it’s not only tertiary care that we can rely on. We have a connection to research, clinical trials and clinical intervention. It doesn’t get any better” (Evans, 2015).

Table 4 presents the full timeline of acquisitions, their locations, and their strategic value.

| Activity | Name | Reason | Location (NY) | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | |||||

| Acquisition | Our Lady of Mercy | Bankruptcy | Westchester | Renamed Montefiore Wakefield | Montefiore: Montefiore Adds North Division (2008) |

| 2013 | |||||

| Acquisition | Westchester Square Medical Center | Bankruptcy | Westchester | Renamed Montefiore Westchester Square with 586 layoffs announced in March | NY Daily News: Sale of Westchester Square Medical Center to Montefiore approved Thurdsay by federal bankruptcy judge (2013) Pitchbook: Montefiore Westchester Sq (n.d.) American Hosp Directory: Montefiore Westchester Sq Campus (n.d.) |

| Acquisition | Sound Shore Health System: – Sound Shore Medical Ctr – Mount Vernon Hospital – Schaffer Extended Care |

Bankruptcy | Westchester New Rochelle Mount Vernon New Rochelle |

Sound Shore renamed Monteriore New Rochelle Hospital | Cision: Sound Shore Health System Reaches Agreement For Montefiore To Acquire Its Assets (2013) Becker’s Hospital Review: Montefiore Medical Center to Acquire Bankrupt Sound Shore Health System (2013) |

| 2014 | |||||

| Affiliation | White Plains Hospital | Tertiary hub, complementary strengths | White Plains | White Plains Daily Voice: Montefiore Health System and White Plains Hospital Sign Formal Agreement (2014); White Plains Hospital: Montefiore-White Plains Hospital Partnership Final(2015) | |

| 2015 | |||||

| Acquisition | Nyack Hospital | Economies of scale | Nyach | Montefiore: History and Milestones (n.d.) Montefiore Nyack: Who We Are (n.d.) |

|

| Affiliation | Saint Joseph’s Med Ctr (St. Vincent’s Hospital Westchester Division) – Inpatient acute care – Senior housing |

Complementary strengths | Yonkers | Montefiore: Montefiore and Saint Joseph’s Enter Clinical Affiliation to Enhance Patient Care (2015) Saint Joseph’s Medical Center: About Us (n.d.) |

|

| Partnership | White Plains’ Burke Rehabiliation Hospital | Complementary strengths | White Plains | Montefiore: History and Milestones (n.d.) Burke Rehabilitation Hospital: About Us – General Information (n.d.) |

|

| Partnership | St. Luke’s Cornwall | Financially struggling | Newburgh | Montefiore: History and Milestones (n.d.) American Hospital Directory: Montefiore St. Lukes Cornwall (n.d.) Modern Healthcare: Montefiore to acquire struggling Hudson Valley hospital (2015) |

|

| Absorption | Albert Einstein College of Medicine | Bronx | Montefiore: History and Milestones (n.d.) | ||

| Affiliation | Saint John’s Riverside Hospital | Complementary strengths | Yonkers | Montefiore: Montefiore To Enhance Patient Care In Yonkers Through New Partnership With St. John’s Riverside Hospital (2015) American Hospital Directory: Saint John’s Riverside Hospital (n.d.) |

|

| 2016 | |||||

| Letter of Intent to explore closer integrated relationship | St. Barnabas Hospital | Complementary strengths | Bronx | Montefiore: Joining Forces to Provide the Best Health Care in the Bronx (2016) | |

| 2018 | |||||

| Acquisition | Crystal Run | “to deliver advanced care that’s unavailable locally” (also financially struggling) | Middletown | Times Herald-Record: Crystal Run-Montefiore merger finalized (2018) | |

| Acquisition | St. Luke’s Cornwall | Financially struggling | Newburgh | Becker’s Hospital Review: Montefiore Health System acquires second hospital in 1 month (2018) Times Herald Record: St. Luke’s Cornwall Hospital joins Montefiore Health System (2018) |

|

| 2019 | |||||

| Closure | Mount Vernon Hospital | Westchester | To be replaced with emergency facility | Becker’s Hospital CFO Report: Montefiore to close 121-bed hospital in New York (2019) | |

| 2020 | |||||

| Acquisition | Saint John’s Riverside Hospital | Yonkers | Delayed by Coronavirus | Lohud: Coronavirus delays move toward St. John’s hospital in Yonkers, Montefiore merger | |

| Acquisition | Saint Joseph’s Medical Center | Yonkers | Delayed by Coronavirus | Lohud: Coronavirus delays move toward St. John’s hospital in Yonkers, Montefiore merger | |

*Note: The order of events may not be exact due to variation in deal disclosure by local news sources. Some news outlets announced the deal when it was approved by the bankruptcy court, others announced it when it was first publicly disclosed, and few included the date the acquisition actually occurred.

Outcomes: Scale, Scope, Financials, and ACO Care Metrics

Scale and scope. As a result of its expansion strategy, Montefiore’s health system grew between 2010 and 2018 from 4 hospitals to 10 (11 in 2019). It also includes 250 ambulatory centers, a nursing home, a home care agency, and a new Hutchinson Campus hospital with no beds across four counties in the region – Bronx, Westchester, Rockland, and Orange counties (Dryda, 2019; Senate Finance and Assembly Ways and Means Committee, 2018). These four counties cover about four million people in total, and of the patients that Montefiore sees, 75 percent are covered by Medicaid and Medicare, accounting for 68 percent of revenue. Among its outpatient facilities in these counties, 54 percent of visits are Medicaid reimbursed and 10 percent of visits are uninsured. Montefiore has become the eighth largest employer in NYS with 40,000 employees – up from 18,000 in 2010. Fifty-five percent of employees are represented by either the 1199SEIU or the NYS Nurses Association and who are all paid at least $15 an hour (NYS Senate Finance and Assembly Ways and Means Committee, 2018; Montefiore Medical Center, 2017). The number of physicians increased from 1,800 to 3,100 (See Table 6).

| Montefiore | Steward | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2010 | 2019 | 2010 | 2019 |

| # of Hospitals | 4 | 11 | 6 | 35 |

| # of States | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| # of Employees | ~18,000* | >40,000 | 12,000 | 42,000 |

| # of Physicians | ~1,800* | 3,100 | 2,305 | 4,800 |

| *2012 data, couldn’t access 2010 data Sources: 1 – Our Company: About Steward 2 – Caritas Christi Health Care Wikipedia 3 – Montefiore 2012 Annual Report 4 – Montefiore State Budget Testimony 2018 – 2019 |

||||

Financials. Montefiore reports relatively stable financials in the face of its expansion, with a 2018 operating margin of 0.89 percent (Gooch, 2019a). This may seem low considering the median operating margin for non-profit hospitals in 2018 was 2.1%; however, among BBB rated hospitals such as Montefiore, the average was negative 0.7 percent (Paavola, 2019a). S&P Global Ratings assigned Montefiore’s bonds as triple B because of the health system’s strong enterprise system, leading market share, reputation, expansive network, and strong management team (Paavola, 2018). Montefiore’s thin operating margin also comes in the face of cuts to federal funding and no increases to Medicaid payment rates in over a decade. Then CEO Steven Safyer stated in 2018 that $40 million was eliminated from Montefiore’s budget because of these cuts (Senate Finance and Assembly Ways and Means Committee, 2018). Hospitals with larger Medicaid and Medicare payer mixes are experiencing decreased operating margins in the face of rising operating costs and rising shares of patients covered by Medicaid and Medicare. Montefiore’s operating revenue of $48.6 million in the first half of 2018 decreased to $22 million in the first half of 2019 – an almost 55 percent drop (Gooch, 2019b). The 2018-2019 NYS budget included the Health Care Shortfall Fund in preparation for further potential cuts, but Safyer claimed at the time that additional Medicaid funding is needed (Senate Finance and Assembly Ways and Means Committee, 2018).

On the flip side, while Montefiore’s operating income decreased, its net income increased from $93.1 million in the first half of 2018 to $100.9 million in the first half of 2019 – an 8.5 percent increase (See Table 7). This is because 80 percent of Montefiore’s income in 2019 was attributed to non-operating sources of revenue (Gooch, 2019b). This use of alternative revenue sources beyond core operations and M&A activity has become increasingly common among large hospital systems that experience diminishing returns in an increasingly consolidated healthcare market (Kacik, 2019). A central question is whether hospitals use these strategies to complement their operations to improve the healthcare system or not. Montefiore appears to be reinvesting money back into the community through its community outreach and other initiatives.

| Financials (FY 2018): | Montefiore* | Steward* |

|---|---|---|

| Operating Revenue | $5,908,072,000 | $6,626,200,000 |

| Net Assets | $1,126,885,000 | ($1,209,600,000) |

| Net Income | $121,200,000 | ($271,100,000) |

| Total Margin | 2.75% | -4.10% |

| Operating Margin | 0.89% | -4.20% |

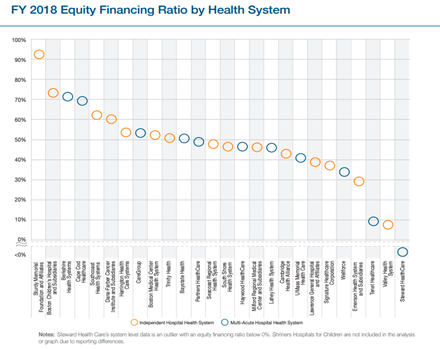

| Equity Financing Ratio | 23.80% | -37.60% |

| * The total margin for Montefiore is estimated based on FY 2018 net income divided by 2018 Q3 revenues because FY 2018 revenue data was not available; the actual total margin would therefore be slightly smaller. Sources: Consolidated Financial Statements (Unaudited) Montefiore Health System, Inc. For the Years Ended December 31, 2019 and 2018; Gooch, 2019). ** The Steward financials are for its Massachusetts system only. Sources are: Massachusetts Acute Hospital and Health System Financial Performance: FY 2018; Paavola, 2019b) | ||

Montefiore’s 2018 financial statements also show a 23.8 percent equity financing ratio, indicating that Montefiore’s use of equity to fund its assets outweighs its use of debt (Montefiore Health System, 2020). The equity ratio is an important indicator of the long-term financial health of a company and its ability to pay off its debts. A positive ratio indicates that Montefiore is not overly leveraged and therefore does not face a threat of financial distress.

Pioneer ACO Outcomes and Patient Care Quality. Even though Montefiore undertook a rapid and costly expansion drive, including the integration of three bankrupt and one financially struggling hospital into its system, it was still accredited as a Pioneer Accountable Care Organization (ACO) under the ACA – one out of only 32 nationwide 3. Of the 32 Pioneer ACOs approved in 2012, only nine survived to the program’s completion in 2016 (CMS, n.d.-a). Montefiore’s Pioneer ACO quality score grew in that time period, reaching 92.6 percent in 2015, a 6 percent increase over the prior year (Montefiore Medical Center, 2016). Montefiore attributes the high rating to higher scores for communication and overall ratings for providers as well as gains in preventative health quality metrics, such as breast cancer screening, new guidelines for hypertension patients, and increased flu vaccinations (Montefiore Medical Center, 2016).

New York State also designated Montefiore in 2018 as a value-based contractor under the State’s Innovator Program, which enables it to increase the number of individuals it manages under its managed care program. Contractors approved as Innovators are able to take on more management functions and thus, are eligible for an increased contribution to providers’ health savings account (NYS Department of Health, 2018).

In addition to high patient quality care scores from its ACO participation, Montefiore continues to rank in the top one percent of hospitals by U.S. News & World Report for complex specialty care in cancer, cardiology and heart surgery, and neurology and neurosurgery, among others, and has been recognized as High Performing in a variety of specialty practices. Montefiore’s quality score ratings have held even as its geographic footprint, and the number of patients that fall within it, has increased (Montefiore Health System, 2019a).

The Steward Health Care System, begun with the purchase of the Caritas Christi Health System by Cerberus Capital Management in 2010, consisted of six core hospitals serving five counties outside of Boston. At the time, Steward’s catchment area was twice the size of Montefiore’s. The average household income was about $72,000 (almost twice as high as that in the Bronx); its poverty rate of 12.2 percent was considerably lower than the Bronx, at 27 percent; and its Medicaid eligible population, also considerably lower (29.8 percent versus 43 percent) (See Table 2). Nonetheless, relative to other parts of Boston, it served the lower income communities in the metropolitan and nearby areas.

Ownership, Mission, and Governance

Like Montefiore, the six Caritas Christi hospitals that Steward began with also have deep institutional legacies of serving the poor that date to the late 19th and early 20th centuries when they were founded by Catholic religious orders 4. In 1985, the Archdiocese of Boston created the Caritas Christi system as one corporation with a non-profit 501(c)3 status; it became the second largest hospital group in New England. At the time Cerberus acquired the system in 2010, it included 1,552 hospital beds and reported serving 55 communities in southern New Hampshire, eastern Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. It also included a Visiting Nurse Association (VNA), at-home hospice care, Laboure College (which trains nurses and health professionals), and Por Cristo (an international relief agency). Of particular importance, the 1,100-member Caritas Christi Network Services (CCNS) was the second-largest physician network in Massachusetts (Coalition, 2010). It reported a workforce of 12,000 healthcare workers, including 400 employed doctors (Caritas Christi Healthcare, n.d.). It also includes St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center, affiliated with Tufts University (Coalition, 2010).

Caritas faced serious financial challenges during the 2008 financial crisis, and in that year, it hired Ralph de la Torre – an MIT trained engineer and a cardiac surgeon who had been CEO of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center’s Cardiovascular Institute (Becker’s Hospital Review, 2017). de la Torre’s vision for a community-based healthcare system was like that of Safyer’s: a commitment to quality healthcare for low-income communities. His strategy for reviving Caritas was two-fold: provide high quality care at a lower price than Caritas’s Boston competitors and form an integrated network of community care hospitals to serve patients more effectively – especially as healthcare continued to shift from a fee-for-service to fee-for-value model that emphasized preventative and high quality of care over quantity of services.

In 2009, under the guidance of de la Torre, Caritas continued its move towards a fee-for-value model when it signed a five-year alternative quality contract with Blue Cross Blue Shield (Weisman, 2009a). Blue Cross Blue Shield’s alternative quality contract is a capitation contract, similar to those negotiated by Montefiore in which the hospital keeps the gains but eats the costs if it goes over budget. Through this payment system and other efforts, Caritas was able to return to profitability in 2009 with a $31.1 million profit (Weisman, 2009b). Reflecting this major swing (from -$20 million in 2008), Moody’s Investor Service upgraded Caritas’ bond rating in January of 2010 from Baa3 to Baa2 based on its strong management and strategic plan (Coalition, 2010; Moody’s Investor Services, 2010)5. de la Torre funneled these funds towards attracting physician practices (Syre & Farrell, 2014).

de la Torre, however, also inherited significant debt as well as a roughly $200 million liability in an underfunded union pension fund. He believed he needed private equity financing in order to achieve his strategic vision; and on March 25, 2010, signed a no-bid contract with Cerberus for a $420 million leveraged buy-out. (Note that President Obama signed the ACA into law on March 23, 2010, which many private equity firms viewed as a green light for profitable investments in hospitals). Surprisingly, Moody’s bond rating of Caritas remained unchanged with the announced buyout (Moody’s Investor Services, 2010). The Massachusetts AG’s office held hearings in June 2010, as the conversion of the non-profit to for-profit status needed approval from the AG, Massachusetts Public Health Council, and the Massachusetts Supreme Court.

Opposition from the public and the medical community mounted quickly, with the formation of a Coalition to Save Catholic Health Care (Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 2015). Even before the June meetings, one of the attorneys representing Caritas sent a letter of dissent to the AG’s office. The coalition argued that the financial condition of the Caritas was improving (based on the 2009 profits and the 2010 Moody’s upgrading) and that Caritas had not sufficiently explored other alternatives. They estimated that patient costs would increase by at least $103 million per year due to the shift in tax status from non-profit to for-profit – as well as due to the need for Cerberus to deliver investor returns; and that after the three-year moratorium, hospitals could be sold or closed. They highlighted the lack of transparency in the no-bid process, including the fact that de la Torre had contributed to the AG Martha Oakley’s election campaign, and that she should have recused herself from the decision. They argued that Cerberus had no experience in running hospitals, no commitment to the Catholic identity of Caritas hospitals, and that the takeover would undermine Caritas’ Catholic social mission and its commitment to low-income communities for over 100 years (Coalition, 2010).

Given these concerns, the AG’s ultimate agreement (October 2010) included four conditions. Cerberus agreed to pay off Caritas’ debt (roughly $275 million) and assume Caritas’ full pension liability (some $200 million); to invest $400 million in capital expenditure; not to close, sell, or transfer majority ownership for 3 to 5 years; and not to take on additional debt for three years if it sought to pay the private equity firm and investors a dividend. These conditions placed unusual constraints on the kinds of financial methods private equity firms often use to extract money from their portfolio companies. Overall, the AG stipulations brought the total cost of the deal to $895 million. Cerberus contributed $245.9 million in equity to the $420 million purchase price and assumed $475 million in debt (Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 2015:35; PitchBook, 2016).

Governance Structure

Most of the hospitals in the Caritas system historically were governed by the Catholic orders that founded them. When the Archdiocese formed the Caritas system in 1985, it established a governing board that was dominated by members of the clergy, who apparently were very involved in the operations – so much so that in 2008, the Massachusetts AG insisted that Caritas form an independent Board of Governors. In May 2008, immediately after Ralph de la Torre became CEO, Caritas reached agreement with the AG to “create a substantially independent Board of Governors,” with the Archdiocese providing religious oversight but no day-to-day involvement in management (Coalition, 2010). This suggests that the AG (and possibly de la Torre) was concerned that Caritas did not have a sufficiently independent board to monitor the strategic direction and decisions of the system, which may have led to some of its financial problems. It also suggests that de la Torre wanted to make sure he had a sufficiently independent board so he would not be subject to the dictates of the Archdiocese.

Once the Cerberus buyout occurred, the board composition did change dramatically – with GPs of Cerberus assuming five of the seven board seats; only Ralph de la Torre had a medical background (Table 3). This new composition hardly represented ‘independence’ from the owners of the system. It contrasts with Montefiore in several respects. First, only de la Torre could provide medical expertise. Second, the Cerberus board domination meant it had virtually complete control over the strategic direction of the system and that the financial logic of the private equity firm would dominate. And third, the board lacked the kind of external networks – both politically and in the healthcare industry – to provide the kind of resources and support that Montefiore could draw on. Thus, in terms of the level of independence and the composition of the board, Steward’s board was inconsistent with the leading research on this topic.

Vertical and Horizontal Integration: An Ad Hoc Debt-driven Model

Vertical integration. Like Montefiore, the Caritas System had undertaken vertical integration of physicians as employees and as part of its independent physician network over a couple of decades, as noted. Post-buyout, Steward increased its number of employed physicians from 445 in 2010 to 604 in 2012 (an increase of almost 36 percent), which led to a 70 percent increase in individual patient claims billed by the hospital physicians. It aggressively acquired a number of physician practices, including Physician’s Healthcare ($8.6 million in cash), Compass Medical ($16.6 million cash), Hawthorn Medical Associates ($31.3 million in cash), and various other physician practices ($6.8 million). The Steward physician network grew to one of the largest in Massachusetts – from 1,617 in 2010, to 2,384 in 2012 (a 47 percent increase). The total Steward workforce grew from 12,000 to over 15,000, or 10,095 full-time equivalents (a 38 percent increase) (Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 2015:18). In 2016, Steward also purchased the Central Massachusetts Independent Physician Association in a leveraged buy-out, in preparation to expand its accountable care model (PitchBook, n.d.-a).

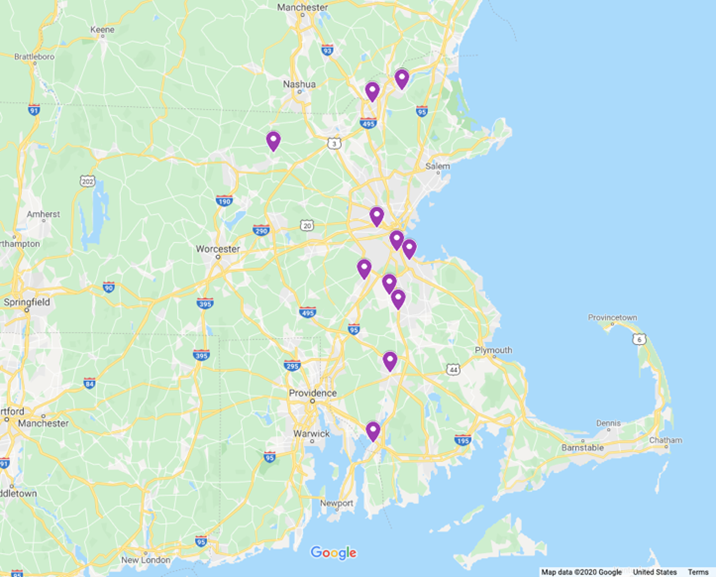

Horizontal integration. de la Torre’s horizontal integration strategy also accelerated after the 2010 buyout. Like Montefiore, it first aggressively expanded in the region with a focus on near bankrupt hospitals, acquiring five hospitals in Massachusetts: Nashoba Valley Medical Center, Merrimack Valley Hospital, Morton Hospital, Quincy Medical Center, and New England Sinai Hospital. These acquisitions increased its healthcare network to 11 hospitals and 2,100 hospital beds under management (Weisman, 2013). The total number of patients covered by the hospital system grew to approximately 1.2 million, with 15 percent of patients on Medicaid and 40 percent on Medicare. In 2014, Steward merged Merrimack Valley Hospital with Holy Family Hospital and closed Quincy Medical Center, replacing it with a satellite emergency room, after the hospital was projected to lose another $20 million that year (Holy Family Hospital, 2014; Ronan, 2014). Steward blamed the closure on low reimbursement rates but refused to reveal audited financial statements to the Massachusetts Center for Health Information and Analysis (CHIA) (Ronan, 2014).

| Activity | Name | Reason | Location | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | |||||

| Acquisition | Caritas Christi Health System: – St. Elizabeth’s Med. Ctr – Carney Hospital – Good Samaritan Med. Ctr – Holy Family Hospital – Haverhill – Holy Family Hospital – Methuen – Norwood Hospital – Saint Anne’s Hospital |

Financially struggling | Boston, MA | Bought by Cerberus, renamed Steward in 2010 | Fierce Healthcare: Acquisition of Caritas Christi Now Complete (2010) |

| 2011 | |||||

| Acquisition | Nashoba Valley Med. ctr. | Ayer, MA | The Boston Globe: Steward reshapes Mass. health care business (2013) | ||

| Acquisition | Merrimack Valley Hospital | Haverhill, MA | The Boston Globe: Steward reshapes Mass. health care business (2013) | ||

| Acquisition | Morton Hospital | Financially struggling | Taunton, MA | The Boston Globe: Steward reshapes Mass. health care business (2013) | |

| Acquisition | Quincy Med. ctr. | Bankruptcy | Quincy, MA | The Boston Globe: Steward reshapes Mass. health care business (2013) | |

| 2012 | |||||

| Acquisition | New England Sinai Hospital | Stoughton, MA | The Boston Globe: Steward reshapes Mass. health care business (2013) | ||

| 2014 | |||||

| Merger | Merrimack Valley & Holy Family Hospital | Puts hospitals on stronger financial footing | Haverhill, MA | Holy Family Hospital: Merrimack Valley Hospital and Holy Family Hospital to Merge (2014) | |

| Closure | Quincy Med. ctr. | Low reimbursements | Quincy, MA | Converted to ER | Quincy Wicked Local: Quincy’s 124-year-old hospital shuts its doors (2014) |

| 2016 | |||||

| Sale-lease back | Med. Properties Trust | Modern Healthcare: Steward says $1.25 billion real estate deal will fund national expansion (2016); Pitchbook: Med. Properties Trust | |||

| Acquisition | Central Mass. Independent Physician Association | Pitchbook: Central Massachusetts Independent Physician Association | |||

| 2017 | |||||

| Acquisition | Community Health Systems: 8 Hospitals – Wuesthoff Health System-Melbourne – Wuesthoff Health System-Rockledge – Sebastian River Med. ctr. – Northside Med. ctr. – Trumbull Memorial Hosp. – Hillside Rehab. Hosp. – Sharon Reg. Health – Easton Hospital |

Hospitals financially struggling; Incorporate into integrated care model |

Melbourne, FL Rockledge, FL Sebastian, FL Youngstown, OH Warren, OH Warren, OH Sharon, PA Easton, PA |

Wuestoff – Melbourne renamed Melbourne Reg. Med. Ctr.; Wuestoff – Rockledge renamed Rockledge Reg. Med. Ctr. |

Modern Healthcare: CHS sells eight hospitals to Steward Health Care (2017) Steward: Our Network (n.d.) |

| Acquisition | IASIS Healthcare: 18 Hospitals – Mountain Vista Med. Ctr. – St. Luke’s Behavioral Health Ctr. – St. Luke’s Med. Ctr. – Tempe St. Luke’s Hospital – Wadley Reg. Med. Ctr. at Hope – Pikes Peak Reg. Hospital – Glenwood Reg. Med. Ctr. – Med. Ctr. of SE Texas – The Med. Ctr. of SE Texas – Victory Campus – Odessa Reg. Med. Ctr. – SW General Hospital – St. Joseph Med. Ctr. – Wadley Reg. Med. Ctr. – Davis Hospital & Med. Ctr. – Jordan Valley Med. Ctr. – Jordan Valley Med. Ctr. – West Valley Campus – Mountain Point Med. Ctr. – Salt Lake Reg. Med. Ctr. |

Bargaining power with suppliers and managed care business | Mesa, AZ Phoenix, AZ Phoenix, AZ Tempe, AZ Hope, AR Woodland Park, CO West Monroe, LA Port Arthur, TX Beaumont, TX Odessa, TX San Antonio, TX Houston, TX Texarkana, TX Layton, UT West Jordan, UT West Valley City, UT Lehi, UT |

Med. Ctr. of SE Texas – Victory Camp. renamed Med.l Ctr. of SE Texas Beaumont Campus – incl. under Med. Ctr. of SE Texas | Steward: Steward Health Completes Acquisition of Iasis Healthcare (2017) |

| 2018 | |||||

| Sale | Pikes Peak Reg. Hospital | Woodland Park, CO | Sale of Pikes Peak to UCHealth | The Gazette: UCHealth acquiring Pikes Peak Reg. Hospital in Woodland Park (2018) | |

| Acquisition | Gozo General Hospital | Looking to expand reach abroad | Malta | FierceHealthcare: Steward Health Care goes international, partners with Malta’s government to operate hospitals (2018); Steward Health Care Malta: Gozo General Hospital (n.d.) | |

| Acquisition | Karin Grech Hospital | Looking to expand reach abroad | Malta | FierceHealthcare: Steward Health Care goes international, partners with Malta’s government to operate hospitals (2018) | |

| Closure | Northside Reg. Med. Ctr. | Underutilization and decline in patient volume | Youngstown, OH | 468 total layoffs | Becker’s Hospital Review: Steward Ohio hospital ups layoffs to 468 as closure looms (2018) Becker’s Hospital Review: Steward to close Ohio hospital, lay off 388 (2018) |

| 2019 | |||||

| Acquisition | Scenic Mountain Med. Ctr. | Big Spring, TX | Steward: Steward Health Completes Acquisition of Scenic Mountain Med. Ctr. (2019) | ||

| Reopening | Florence Hospital | Anthem, AZ | Becker’s Hospital Review: Steward to reopen Arizona hospital (2018); American Hospital Directory: Florence Hospital at Anthem (n.d.) | ||

| Closure | St. Luke’s Med. Ctr. | Underutilization | Phoenix, AZ | 655 total layoffs | Phoenix Business Journal: St. Luke’s trying to find jobs for displaced workers at other facilities (2019) |

| 2020 | |||||

| Sale | Easton Hospital | Easton, PA | Becker’s Hospital Review: Steward sells Pennsylvania hospital, saving closure (2020) | ||

| Closure | Quincy ER | Developer terminated lease | Quincy, MA | Quincy Wicked Local: Qincy ER to close in November after developer terminates lease (2020) | |

*Note: The order of events may not be exact due to variation in deal disclosure by local news sources. Some news outlets announced the deal when it was approved by the bankruptcy court, others announced it when it was first publicly disclosed, and few included the date the acquisition actually occurred.

Figure 2: Steward’s Expansion in Massachusetts, 2011-2013

Here is where the parallel stories of Montefiore and Steward and their regional M&A expansion strategies diverge. First, Cerberus was under pressure to pay back investors in a three- to five-year window; but the Massachusetts AG withheld its license to sell within a three- to five-year window or to load the system with additional debt to pay dividends. Cerberus, however, did cut costs to improve operational efficiency and monetized assets wherever possible: leasing out real estate, selling off lab and ambulance services, outsourcing security staff, and reducing staffing (Weisman, 2013). Second, both Montefiore and Steward initially focused on acquiring struggling hospital systems; however, Steward’s intent behind this was to test out its managed care plan with the long-term goal of replicating it on a national, and later global, level. After five years of acquisitions, reorganizations, and cost-cutting efforts, Steward stated that it had built a “scalable community-based integrated ACO delivery system” that could successfully operate under a value-based model and turn a profit while still supporting local communities and producing better patient outcomes (Steward Health Care System, 2018). It just needed the necessary amount of funding and an extensive physicians’ network to match its ambitions.

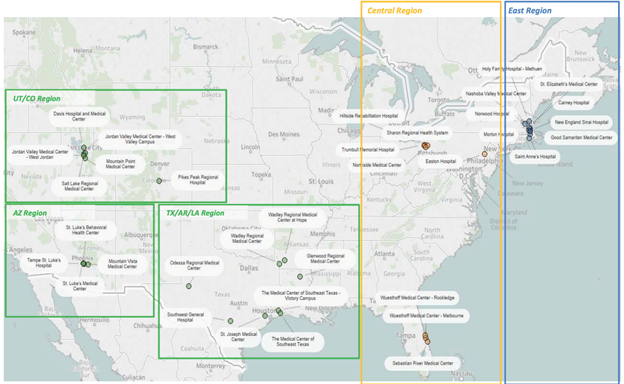

After the end of the 5-year period in which the Massachusetts State AG monitored Steward’s compliance with the conditions of the Caritas sale, Cerberus started using classic PE financial strategies. In 2016, Steward sold a large number of its hospitals’ properties to Medical Properties Trust (MPT), a real-estate investment trust (REIT), for $1.25 billion in a sale-leaseback transaction in which the hospitals must now pay rent on buildings they previously owned. Cerberus would use the sale proceeds to pay dividends to itself and its investors – $484 million to one Cerberus fund alone. It also used the money to finance a massive national expansion effort (Hechinger & Willmer, 2020). MPT also invested an additional $50 million in Steward for a 5 percent equity stake (Castellucci, 2016; PitchBook, n.d.-d). REITs have increasingly invested in the $1 trillion healthcare real-estate industry, promoting themselves as a more immediate source of capital for hospitals to use (or in this case the PE firm) when they sell them their property – despite the fact that hospitals then must pay rent in long-term leases (Barkholz, 2016b).

Steward’s homepage boasts its “asset-light” business model where “we lease our hospitals rather than own them, ensuring that our top service and priority is providing great care” (Steward, n.d.-b). Notably, however, hospitals have good reason to own their own property – to hedge against economic downturns like the 2008 recession or the Covid-19 pandemic. As of mid-2020, Steward hospitals with extended lease agreements – such as the Quincy Medical Center emergency room – were facing pressure from some property management companies to either close or sell (Ellison, 2020a). The real long-term burden for the Steward hospitals is their future lease payments, which in 2018 stood at $3 billion (Hechinger & Willmer, 2020).

By February of 2017, Steward began rapidly buying up hospital systems across the country while MPT acquired the real estate from Cerberus, often repaying to the PE firm nearly the full acquisition costs. There was no apparent healthcare logic to the acquisitions, but rather financial. Steward, for example, bought eight hospitals (in Florida, Ohio, and Pennsylvania) in a fire sale from the heavily indebted Community Health Systems (CHS) (Barkholz, 2017). CHS had become one of the largest national for-profit systems by using the PE leveraged buyout strategy; but by 2014, it had to sell off 50 of its 206 hospitals due to unsustainable debt (Barkholz, 2016a). Steward was adopting the CHS debt-driven acquisition strategy right at the time the strategy had proven disastrous (Appelbaum & Batt, 2020: 21-27). In May, Steward bought IASIS Healthcare (previously PE-owned) in a $1.9 billion leveraged buyout – picking up scattered hospitals in Arizona, Arkansas, Louisiana, Texas, and Utah – and increasing its estimated revenue from $3.7 to $6.6 billion (Paavola, 2019b). MPT contributed $1.4 billion to the deal and Cerberus investors made up the rest (Bartlett, 2017). The deals allowed Steward to build market power with suppliers and to acquire the managed care business of IASIS, which accounted for $1.29 billion of the company’s $3.25 billion total revenue (Kacik, 2017).