Based on assessments made by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and credit rating agencies, this brief identifies 79 countries as being at risk of or in debt distress. Sixty of these countries are also considered highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Tighter global financial conditions as a result of interest rate hikes by the United States and other high-income countries are increasing debt service costs for developing countries. In addition to higher interest rate costs, the rate hikes in the United States put pressure on the currencies of developing countries, increasing capital flight and the risk of currency depreciations that further raise the cost of servicing foreign currency–denominated debts.

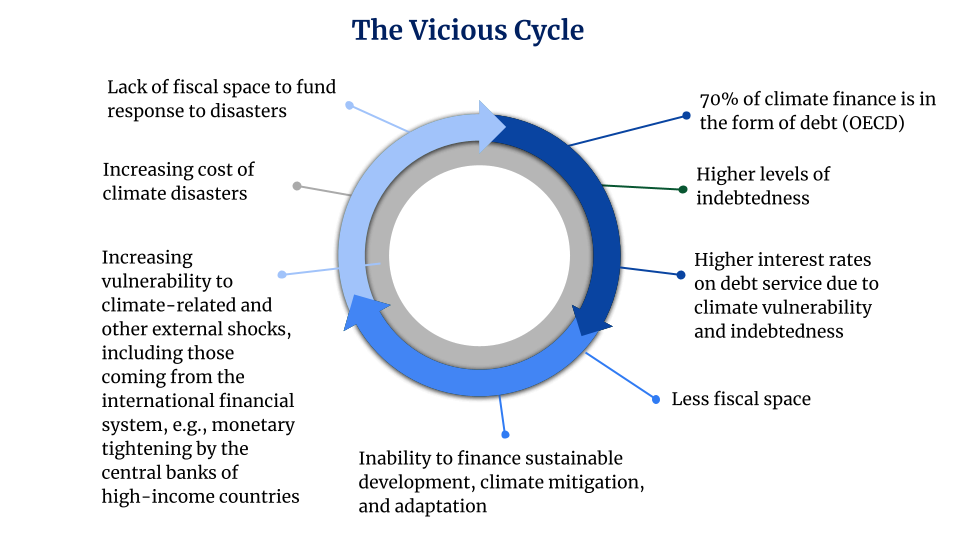

This brief provides an overview of the creditor profiles and debt service burdens for developing countries, focusing on their foreign currency debts owed to external creditors. The findings highlight the burden of servicing these debts and the lack of options to seek relief, as a result of which many countries are unable to invest in urgent climate and development priorities. Developing countries can find themselves trapped in a vicious cycle in which investments in resilience are postponed in favor of debt service, which in turn makes them more vulnerable to climate impacts and delays development efforts, rendering these countries unprepared to respond to future disasters and perpetuating indebtedness.

To break this cycle, more ambitious solutions to support these countries are needed. Such solutions include a comprehensive sovereign debt restructuring mechanism, new sustainable sources of financing, and measures such as a new allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) and a suspension of IMF surcharges, which can provide immediate relief.

Interest rates are expected to remain higher for longer periods of time, with central banks in the United States and other wealthy countries signaling that they will not lower them quickly. Despite the tighter financial conditions resulting from higher rates, institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are expressing optimism over a “soft landing” for the global economy.1 However, as a recent brief from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) warns, this soft landing does not appear likely to extend to developing countries, which are disproportionately impacted by global spillovers from monetary tightening.2

An unfavorable global economic context of declining medium-term growth rates, low investment, and a weak rebound from the COVID-19 pandemic crisis threatens developing countries’ chances of realizing a sustainable recovery.3 Tighter financial conditions have increased the borrowing and debt service costs in developing countries. For countries with large external debts – denominated mostly in US dollars and owed to creditors abroad – a stronger dollar makes repayment even more costly.4

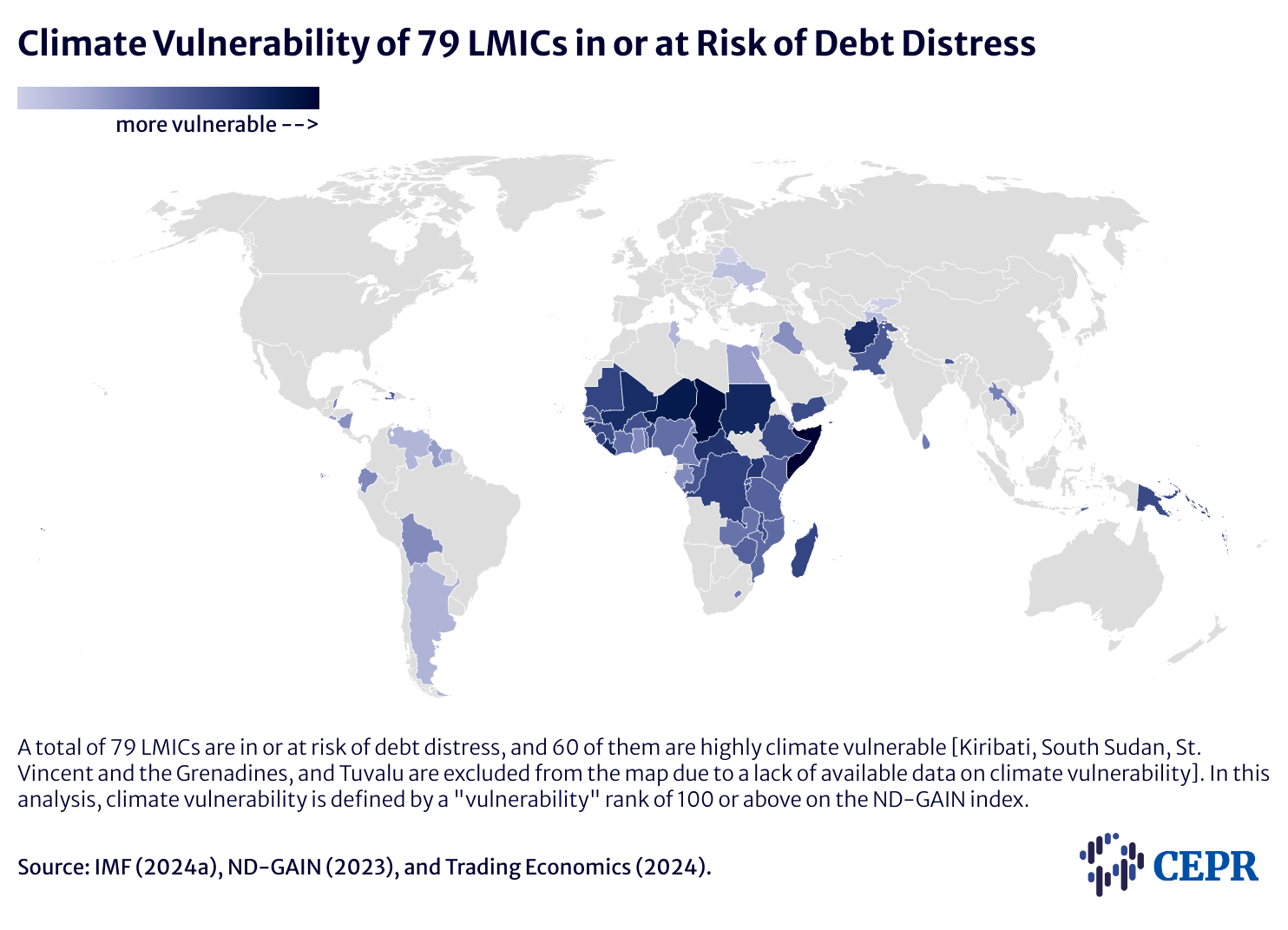

Analyzing available credit assessments made by both the IMF and credit rating agencies, we find that among the 134 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) for which data or credit assessments are available, 79 are considered at risk of or already in debt distress. As shown in Figure 1, there is a substantial overlap between countries that are struggling with debt and those that are also vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Sixty of the 79 countries at risk of or in debt distress are highly vulnerable to climate-related risks.

Figure 1

For many developing countries identified by the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative as being extremely vulnerable to risks stemming from climate change, debt service takes precedence over making the necessary investments in building resilience.

For many developing countries identified by the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative as being extremely vulnerable to risks stemming from climate change, debt service takes precedence over making the necessary investments in building resilience.

Using the World Bank’s International Debt Statistics (IDS), this brief examines the external public sector debt of 122 LMICs for which data are available.5 The brief examines the trends for the entire group and specifically for the members of the Intergovernmental Group of Twenty-Four on International Monetary Affairs and Development (G-24), which coordinates the engagement of developing countries with the IMF and the World Bank.6

External public debt is mostly denominated in US dollars and owed to foreign creditors. It cannot be restructured and addressed domestically, and it often results in the allocation of scarce foreign currency resources directly to creditors and away from investments in climate resilience and other development priorities.7 Additionally, the domestic mobilization of resources to increase investment is needed, but some of the necessary investments require the use of foreign currency to cover the costs of importing certain goods, technologies, or services.

In 2024, external public debt service is projected to exceed the non-climate-related Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) investment needs in 92 LMICs, as shown in Figure 2. Twenty-five out of 29 G-24 countries are included in the analysis. The majority (i.e., 15) will spend more on debt service than on SDG investment needs.

Figure 2

Out of the 92 countries that are projected to spend more on debt service than on SDG investments in 2024, only 61 are part of the group formally recognized as being in or at risk of debt distress. This finding should raise further concern regarding the debt servicing burdens for developing countries and a system in which prioritizing creditors over national priorities is normalized.

High debt service costs prevent countries from making the needed investments to meet their climate and development needs, creating a negative feedback loop. As a result, developing countries are at risk of being trapped in a vicious cycle that blocks progress towards climate action and other SDGs, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Note: Reproduced from Vasic-Lalovic et al. (2023).

Developing countries impacted by large-scale climate disasters are often left with no choice but to borrow funds to respond to these disasters, further deepening this cycle. This issue highlights how an uneven financial architecture disadvantages these countries and increases their debt burdens in response to a crisis that is a result of the substantial historical emissions generated by wealthy countries.8

Currently, higher debt service costs resulting from the monetary policy decisions made in a handful of wealthy countries are further squeezing developing countries and limiting their capacity to undertake long-term investments. Debt pressures and the burdens of debt service are increasing at a time when there is an urgent need to make large-scale investments to address the climate crisis and put the world on track to achieve the SDGs. Multilateral institutions must provide solutions and effective plans to break the vicious cycle and ensure that countries have access to sustainable forms of finance so that they can meet their development goals.

Over the last decade, the share of the external debt of developing countries as a percentage of governments’ borrowing increased from 17 percent to 25 percent. This increase makes these countries more vulnerable to external shocks and currency fluctuations, and it places a larger share of their debt outside of the purview of domestic restructuring measures.9

Countries can borrow externally from official creditors either bilaterally or through multilateral institutions. They can also borrow from private creditors through bond markets and other commercial lenders.10

The shift in creditor composition between 2010 and 2022 for developing countries, excluding China, and for G-24 member countries is shown in Figure 4. Since 2010, the external public debt stock for 118 LMICs, excluding China, more than doubled, increasing from $1.5 trillion in 2010 to $3.1 trillion in 2022. In terms of nominal GDP, the external public debt of these countries was approximately 11 percent of GDP in 2010 and approximately 15 percent, on average, in 2022.11 The debt stock in LMICs grew faster than GDP over this period, on average, representing a significant increase. The growing burden of debt is primarily a result of higher debt service, largely due to the increased interest rates in wealthy countries.12 For members of the G-24, the external debt stock increased from $766 billion in 2010 to $1.7 trillion in 2022. In this time frame, the share of debt held by private creditors increased from 48 percent to 55 percent for all LMICs and from 50 percent to 58 percent for G-24 member countries.

Bilateral creditors, excepting China, have decreased the share of developing country debt that they hold. While the role of China as a creditor to other developing countries increased significantly, overall Chinese bilateral loans account for only a small percentage of total external public debt, with China holding 4.8 percent of the debt for all LMICs and 4.3 percent of the debt for G-24 member countries.

Figure 4

Private creditors lend at market rates, charging higher interest rates than official creditors and higher premiums for lower-income countries. Furthermore, in general, they issue debt with shorter maturities, with the increased cost of debt service worsening the prospects for long-term debt sustainability.13 Since the tightening of global financial conditions, private creditors have taken a step back, with the net flows from this group of creditors becoming negative in 2022.14

The negative flows from private creditors were partially offset by an increase in lending from multilateral creditors, which offer loans at lower rates and on concessional terms for some low-income countries. In an uncertain global context, countries can be expected to increase their reliance on multilateral creditors.

Figure 5

Multilateral lenders currently hold approximately one-third of LMICs’ external debt. Figure 5 shows the breakdown of this debt by region between the major multilateral lenders.

The World Bank’s International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which mostly lends to middle-income countries with market access, is the top multilateral creditor in three out of six regions globally. It accounts for almost one-third of multilateral lending in East Asia and the Pacific and over a quarter in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). The International Development Association (IDA), which is an arm of the World Bank that offers concessional loans and grants to low-income countries, contributes more than one-third of multilateral lending in South Asia and almost half in sub-Saharan Africa.

In addition to the World Bank, each region has other major creditors, such as the Inter-American Development Bank, which holds over 35% of multilateral public debt in LAC, and the Asian Development Bank, which holds 42% of multilateral loans in East Asia and the Pacific.

Multilateral lenders generally offer credit on favorable terms, and multilateral development banks frequently offer interest-free loans or grants to countries that are struggling with high debt burdens. One notable exception is the IMF, which penalizes its most indebted middle-income borrowers with additional fees known as surcharges.

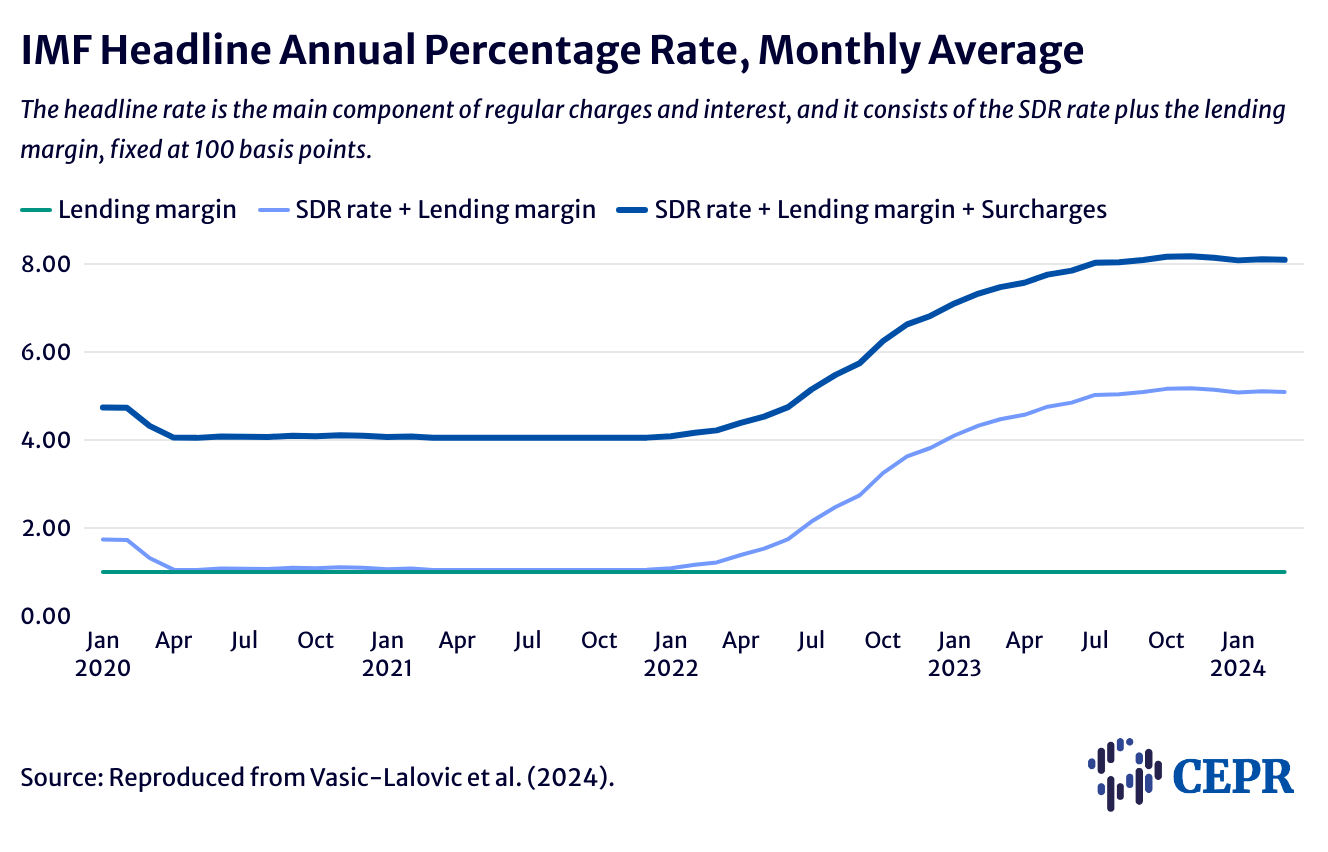

The increasing cost of IMF lending, which adds fees to a benchmark rate that follows the interest rates in the five wealthy countries that constitute its official reserve basket for Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), is shown in Figure 6. The 22 highly indebted countries paying IMF surcharges pay rates that can exceed 8 percent; these fees add $2 billion per year to debt payments.15

Figure 6

The IMF’s surcharge policy significantly increases the debt service for heavily indebted countries, diverting scarce resources from public priorities. In the next five years, 22 countries will spend approximately $10 billion on surcharges alone and on top of regular interest payments to the IMF.16 The number of countries paying surcharges has nearly tripled since 2019, with several more nations at risk of paying these fees in future years.

These figures not only indicate that the burden of surcharges is growing among an increasing number of countries but also suggest that the policy is not effectively achieving its stated goal of discouraging reliance on IMF lending. Furthermore, the IMF does not currently require the income generated from surcharges, as it will exceed its target for precautionary balances, which have largely been funded by surcharges, starting this year.17 By eliminating these fees, the IMF can substantially and immediately decrease the debt service of highly indebted countries.

The IMF could also reduce the debt burden of borrowing countries by cutting its lending margin from 100 basis points, as shown in Figure 6, to 50 basis points. By both decreasing its interest charge and eliminating surcharges, the IMF could lower its effective lending rate from over 8 percent to approximately 4.6 percent for its most indebted borrowers. A failure to eliminate surcharges and reduce the IMF’s fixed lending margin for FY 2024-25 and beyond is a missed opportunity to reduce the debt service burden of indebted countries that face challenges in financing climate action and achieving the SDGs.

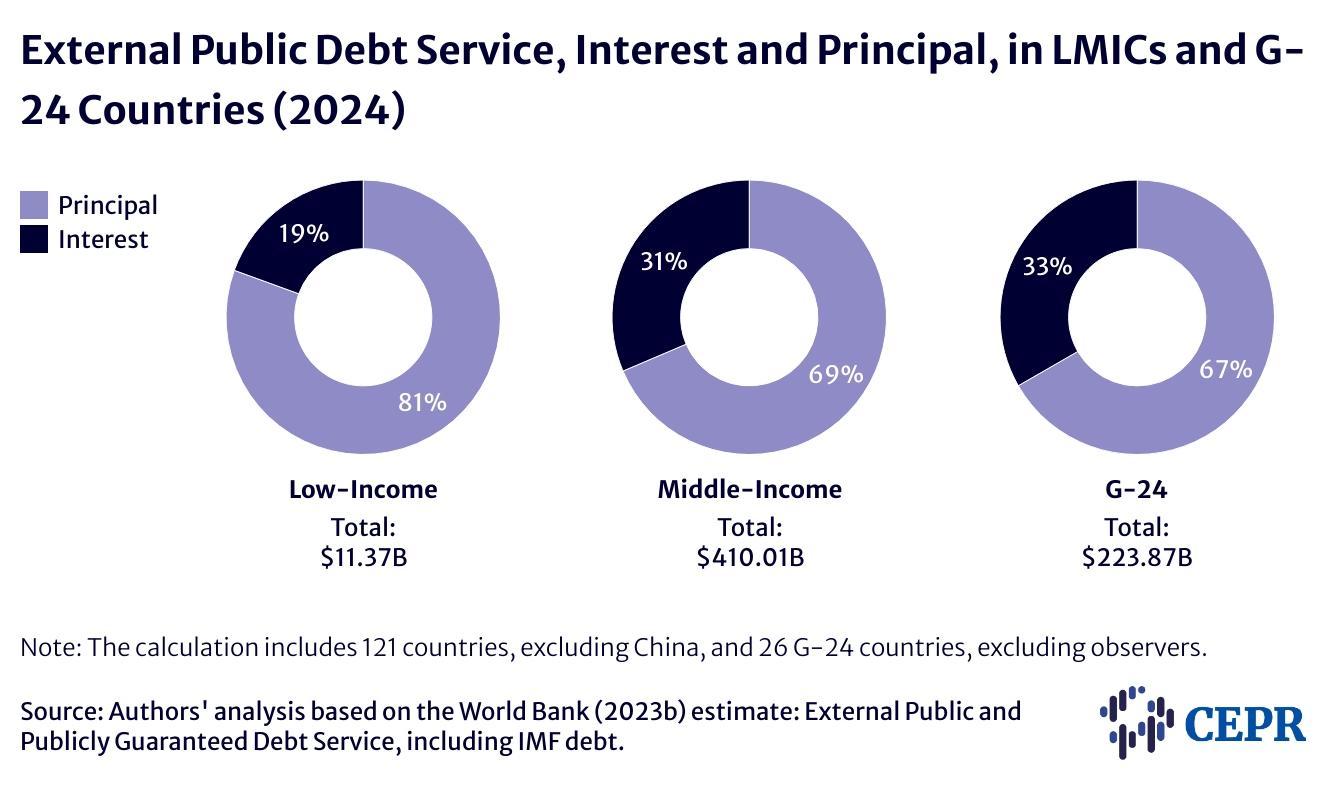

In 2024, developing countries are expected to divert large amounts of their limited financial resources to service their debt, as shown in Figure 7. Low-income countries are estimated to spend a total of $11.4 billion on debt service, with 19 percent of this sum being used for interest alone, and middle-income countries are expected to spend $410 billion on debt service, with 31 percent going to interest payments. For the 26 countries that are included in the data and that are part of the G-24, debt service costs are estimated to be close to $224 billion in 2024, with 33 percent of this sum covering interest payments.

Figure 7

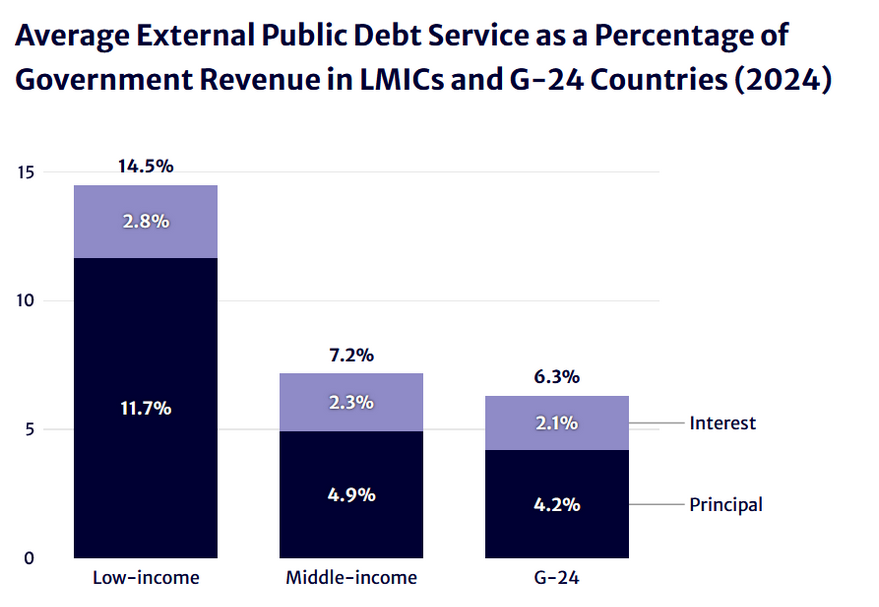

These costs, which do not include debt service for domestically held debt, can represent a significant part of countries’ overall revenue. Figure 8 shows the estimated debt service costs as a percentage of total government revenue.

These costs, which do not include debt service for domestically held debt, can represent a significant part of countries’ overall revenue. Figure 8 shows the estimated debt service costs as a percentage of total government revenue.

For low-income countries, external debt service constitutes an average of 14.5 percent of their entire revenue; for middle-income countries, the amount is 7.2 percent, and for G-24 members, it is 6.3 percent.

Figure 8

For developing countries, debt service is also particularly high relative to their export revenue, which is an important source of foreign currency reserves. When debt payments cut into foreign currency reserves, they can threaten balance of payments stability, and prevent countries from covering the cost of key imports, such as food and medicine. Using projections for export revenues relative to debt service expenditures in 2024, Figure 9 illustrates the estimated external debt service as a share of exports. In 2024, for low-income countries, interest payments alone constitute two percent of export revenue, on average, and overall debt service is approximately 10 percent of export revenue, as shown in Figure 9. For middle-income and G-24 countries, total debt service represents 6.6 and 7.4 percent of exports, respectively, of which 2.1 percent and 2.5 percent cover only interest payments.

Figure 9

Debt amortizations – meaning repayment amounts for principal – are expected to increase significantly over the 2023-2024 period.18 The net flows for borrowers already became negative in 2022, the last year for which complete data are available.19 There are additional risks that can increase the cost of debt service stemming from potential currency depreciations and exchange rate movements, which only worsen for countries that are considered to be at higher risk and that are facing other economic challenges.

Debt amortizations – meaning repayment amounts for principal – are expected to increase significantly over the 2023-2024 period.18 The net flows for borrowers already became negative in 2022, the last year for which complete data are available.19 There are additional risks that can increase the cost of debt service stemming from potential currency depreciations and exchange rate movements, which only worsen for countries that are considered to be at higher risk and that are facing other economic challenges.

World Bank economists warn of 28 low-income countries already in a “debt trap” without a path forward and with many others being likely to follow, as they need external debt relief. However, there is no mechanism in place to deliver such relief in a timely manner.20 Within the current architecture, there are no options to address debt issues on a large scale, and countries seeking relief are individually dragged into long negotiations and suffer prolonged crises.21

Debt-distressed states are generally left with no alternative but to approach the IMF and start an ad hoc process of complex negotiations with individual, uncoordinated creditors.22 To begin restructuring, a government will seek an IMF loan to prevent imminent default or, if already in default, to borrow into arrears. In this case, an IMF loan also serves as a guarantee for other creditors that may not come to the negotiating table otherwise. However, after a lengthy loan approval and negotiation process, there is no guarantee that a government and its external creditors will come to an agreement or that the country will receive any amount of debt cancellation.23

In recent decades, at various points, efforts have been made to establish mechanisms and instruments that can provide debt treatment from different creditors in a more systematic manner. An overview of these initiatives is provided in Table 1.

Table 1: Debt Restructuring Initiatives

Source: Aboneaaj et al. (2022)

In terms of existing efforts to address debt issues, the G20’s Common Framework is the most notable mechanism, involving some of the largest official creditors. However, it directly covers relief negotiations for only a small fraction of overall external debt, namely, official bilateral debt for low-income countries. Most debt falls outside of its purview.24

Three countries are currently pursuing debt restructurings through the Common Framework: Ethiopia, Ghana, and Zambia.25 Zambia is nearing a final agreement, after significant delays, and to date, only Chad has completed restructuring.26 However, Chad’s debt treatment under the framework did not result in any reductions in principal, constituting a deal that “incentivizes the maximization of oil revenues,” thereby undermining the prospect of a fair, green transition.27 As middle-income countries, Suriname and Sri Lanka, which are currently pursuing debt negotiations, did not qualify for the Common Framework.28

In the course of years-long negotiations, the populations of debt-distressed countries often suffer the negative economic consequences of austerity measures attached to IMF loans, such as cuts to basic public services, and they remain vulnerable to climate-related disasters with little chance of sustainable recovery. This situation is illustrated by Zambia, which is entering its third year of restructuring and awaits the finalization of its agreement with creditors, while an ongoing drought seriously threatens national food and energy security.29

Additionally, neither the Common Framework nor ad hoc restructurings can compel private creditors to offer comparability of treatment, which often prolongs debt negotiations further. With repayments not being frozen and interest and fees accumulating on debt considered to be in default, private creditors are not incentivized to agree to meaningful relief, to the detriment of the debt-distressed country.30 A comprehensive sovereign debt resolution mechanism that ensures that debt service is suspended during negotiations for all creditors could provide a potential framework for all creditors to come to the table and seek a timely solution. An important proposal from the UN would ensure that all countries have access to a neutral debt resolution framework in a process that engages all creditor classes at once.31

Unable to ignore the challenging context for many developing countries, the links between climate vulnerability and climate-related losses and damages, and the accumulation of unsustainable debt, international financial institutions and wealthy countries have supported various initiatives presented as solutions to these issues, and they have made various commitments to providing greater financial support.

Wealthy countries, which are historic polluters, have committed to supporting developing countries in addressing the impacts of climate change and supporting their transition processes by channeling resources to support climate finance.32 In practice, most additional financing provided has come in the form of further lending, including for countries that have been affected by major disasters.33 The substantial gap in grant-based climate finance from wealthy nations compels LMICs to borrow to cover the growing costs of climate-related disasters. This borrowing exacerbates their debt burdens, perpetuating a vicious cycle that hinders their advancement towards achieving the SDGs and that undermines their capacity to effectively respond to climate change.

Recent small-scale multilateral initiatives such as debt-for-nature swaps and the Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST) cannot be considered to be solutions to systemic debt or climate issues.34 The IMF created the RST to support countries with long-term climate finance and partially funded the trust by having some wealthy members re-channel their share of the $650 billion allocation of SDRs from 2021 to the RST.35 This facility would provide countries with 20-year loans, and accessing it would be paired with having a concomitant traditional IMF program. The funding from this facility would focus on “reforms” to attract private finance, rather than directly financing climate investments.36

Figure 10 contrasts the resources that could be made available for developing countries from the RST for developing countries and for members of the G-24 with the resources that countries would receive directly from an additional $650 billion allocation of SDRs. A new allocation would provide more debt-free resources, with no strings attached. On the other hand, financing from the RST locks countries into more debt and IMF conditionality while providing less immediate liquidity. Potential lending through the RST, assuming normal access of 0.75 of a country’s quota and a 1 billion cap on loans, means that the RST would provide $73 billion in financing if all eligible countries, excluding China, sought a program. However, those same countries would directly receive resources worth $209 billion without any conditionality attached through a new SDR allocation. For G-24 member countries, the potential RST financing is $26 billion, while their share of a new $650 billion in SDRs is $93 billion.

Figure 10

A new allocation of SDRs is a measure that could be taken immediately to provide relief and increase fiscal space in developing countries. In response to the economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the IMF issued $650 billion in SDRs to its member states in 2021, and it could do so again if there is political will. The 2021 allocation of SDRs increased liquidity worldwide without creating new debt, and it provided LMICs with immediate and effective fiscal relief. The allocation allowed countries to better respond to the external shock of the pandemic by decreasing exchange rate risk, addressing balance of payments constraints, and helping improve borrowing terms.37

A new allocation of SDRs is a measure that could be taken immediately to provide relief and increase fiscal space in developing countries. In response to the economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the IMF issued $650 billion in SDRs to its member states in 2021, and it could do so again if there is political will. The 2021 allocation of SDRs increased liquidity worldwide without creating new debt, and it provided LMICs with immediate and effective fiscal relief. The allocation allowed countries to better respond to the external shock of the pandemic by decreasing exchange rate risk, addressing balance of payments constraints, and helping improve borrowing terms.37

Civil society organizations and political actors, including the UN Secretary General, have repeatedly called for a new allocation of SDRs to address climate and development needs.38 These calls echo those for a large and comprehensive “SDG stimulus” that can ensure that countries can meet the scale of the spending needed.39

For some commentators, the successful issuance of private market bonds by some African countries after a two-year break signals an improving outlook on debt problems.40 These bonds come with high price tags, with many carrying double-digit yields. This worsens debt service burdens and defers real action on debt relief and on ensuring that countries have the fiscal space to pursue urgent priorities.

In the aftermath of the pandemic, the world has moved backward in terms of hunger and poverty levels globally, putting SDG achievement at further risk. The magnitude of climate disasters continues to worsen, but developing countries, which often are most affected by the climate crisis, lack the resources and fiscal space to invest in building resilience and taking adaptation measures. To achieve climate and development goals, multilateral institutions and the global community must step up and offer real solutions to these problems.

This brief highlights the challenging situation that many developing countries find themselves in and the large number of resources that are diverted from national priorities to repay foreign creditors. The burdens of developing countries are worsened by global financial conditions and the interest rate policies of central banks in wealthy countries, with additional risks being added to the stability of the currencies of developing countries.

Coordinated action is urgently needed to ensure that no country is forced to choose between repaying creditors and investing in health care, education, social protection, and climate resilience. Among developing countries, demands for a multilateral sovereign debt restructuring mechanism are once again gaining momentum, as are broader demands for a more just financial architecture.41 Debt relief and the establishment of a mechanism that can provide relief in a timely manner need to be paired with sustainable financing that allows countries to pursue climate and development goals without accumulating further unsustainable debt.

In the meantime, measures such as a new allocation of SDRs and the suspension of surcharges by the IMF can provide some immediate breathing room to struggling developing countries.

Landers. 2022. “The ABCs of Sovereign Debt Relief.” Washington, DC: Center for Global Development. October. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/abcs-sovereign-debt-relief

Adrian Tobias, Gaspar Victor, Grouinchas Pierre-Olivier. 2024. “ The Fiscal and Financial Risks of a High-Debt, Slow-Growth World.” https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2024/03/28/the-fiscal-and-financial-risks-of-a-high-debt-slow-growth-world

Al Jazeera. 2024. “Zambia declares national disaster after drought devastates agriculture.” February 29. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/2/29/zambia-declares-national-disaster-after-drought-devastates-agriculture.

Arauz, Andrés. 2024. “The IMF’s Effective Lending Rate for Large Borrowers Is Now at Over 8 Percent.” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research. March. https://cepr.net/the-imfs-effective-lending-rate-for-large-borrowers-is-now-at-over-8-percent/

Arauz, Andrés and Ivana Vasic-Lalovic. 2024. “No More Excuse for Surcharges: the Target for Precautionary Balances Has Been Reached.” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research. February. https://cepr.net/no-more-excuse-for-surcharges-the-target-for-precautionary-balances-has-been-reached/.

Arauz, Andrés, and Kevin Cashman. 2022. “Special Drawing Rights One Year Later, By the Numbers.” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, August. https://cepr.net/special-drawing-rights-one-year-later-by-the-numbers/.

Bretton Woods Project. 2022. “Chad gets debt rescheduling, not relief, and is left dependent on oil revenues.” https://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2022/12/chad-gets-debt-rescheduling-not-relief-and-is-left-dependent-on-oil-revenues/.

Do Rosario, Jorgelina and Karin Strohecker. 2024. “Zambia strikes preliminary deal on $3 bln international bond rework.” Reuters. March 25. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/zambia-reaches-debt-restructuring-agreement-with-bondholder-committee-2024-03-25/.

Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) 2024. “International Trade: Export Prices.” https://viewpoint.eiu.com/data/.

Elliott, Larry. 2023. “‘It’s not done’: IMF head warns of costs in finally overcoming inflation.” The Guardian. October 5. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/oct/05/imf-head-kristalina-georgieva-warns-of-costs-overcoming-inflation-interest-rates-covid-ukraine-war.

European Network on Debt and Development (Eurodad). 2023. “The Debt Games – Is There a Way Out of the Maze?” Brussels: European Network on Debt and Development. April. https://www.eurodad.org/the_debt_games

Fresnillo, Iolanda. 2023. “Miracle or Mirage: Are Debt Swaps Really a Silver Bullet?” Brussels: European Network on Debt and Development. December. https://www.eurodad.org/miracle_or_mirage

Fresnillo, Iolanda. 2024. “Debt justice in 2024: challenges and prospects in a full-blown debt crisis.” Brussels: European Network on Debt and Development. February. https://www.eurodad.org/debt_justice_in_2024_challenges_and_prospects_in_a_full_blown_debt_crisis.

Georgieva Kristialina. 2023. “Remarks by the IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva at the Paris Summit Closing Press Conference.” June 23. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2023/06/23/sp062323-mdremarks-paris-summit-closing-presser.

Goko-Petzer Colleen. 2024. “Africa’s Eurobond Comeback Ends Debt-Distress Saga.” https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-02-09/africa-s-eurobond-comeback-ends-post-covid-debt-distress-saga?sref=wgSUpWLp

Group of 77 (G-77). 2024. “Third South Summit Outcome Document.” https://www.g77.org/doc/3southsummit_outcome.htm

Intergovernmental Group of Twenty-Four (G-24). 2024. “Mandate.” https://www.g24.org/mandate/

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2021. “2021 General SDR Allocation” August 31. https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/special-drawing-right/2021-SDR-Allocation#footnote.

____. 2022. “Proposal to Establish a Resilience and Sustainability Trust.” April. https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/PP/2022/English/PPEA2022013.ashx.

____. 2023a. “Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust.” March. https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Sheets/2023/Catastrophe-containment-relief-trust-CCRT.

____. 2023b. “Review of the Fund’s income position for FY 2023 and FY 2024.” June. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Policy-Papers/Issues/2023/06/15/Review-of-the-Funds-Income-Position-for-FY2023-and-FY2024-534850.

____. 2023c. “SDR Valuation.” Accessed: March 19, 2024. https://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/data/rms_sdrv.aspx.

____. 2023d. “World Economic Outlook Database.” October 5. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/SPROLLs/world-economic-outlook-databases#sort=%40imfdate%20descending.

____. 2024a. “List of LIC DSAs for PRGT-Eligible Countries.” February 29. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/dsa/dsalist.pdf.

____. 2024b. “World Economic Outlook Update. January.” https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2024/01/30/world-economic-outlook-update-january-2024.

Kenworthy Philip, Kose M. Ayhan, and Nikita Perevavlov . (2024). “A Silent Debt Crisis is Engulfing Developing Economies with Weak Credit Ratings.” World Bank Blog. February 28. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/voices/silent-debt-crisis-engulfing-developing-economies-weak-credit-ratings.

Mariotti, Chiara. (2022). “Why the IMF Resilience and Sustainability Trust is Not a Silver Bullet for Covid-19 Recovery and the Fight Against Climate Change.” Brussels: European Network on Debt and Development. January. https://www.eurodad.org/resilience_and_sustainability_trust_not_silver_bullet_covid19_climate_change

Morsy, Hanan. 2023. “Reforming the Global Debt Architecture.” United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. July 4. https://www.uneca.org/stories/reforming-the-global-debt-architecture.

Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN). 2023. “Country Rankings: Vulnerability.” https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/country-index/rankings/.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2023.” “Climate Finance and the USD 100 Billion Goal.” https://doi.org/10.1787/e20d2bc7-en

Parkin, Benjamin and Jonathan Wheatley. 2022. “Sri Lanka debt talks with China a test of creditor appetite for bailout.” Financial Times. October 7. https://www.ft.com/content/92eebc7d-6710-49d2-81a7-a421f86a840c.

Ramos, Luma, Rebecca Ray, Rishikesh Ram Bhandary, Kevin P. Gallagher, and William N. Kring. 2023. “Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery: Guaranteeing Sustainable Development.” Boston, London, Berlin: Boston University Global Development Policy Center; Centre for Sustainable Finance, SOAS, University of London; Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. April. https://www.bu.edu/gdp/files/2023/05/DRGR_Report_May_2023_FIN.pdf.

Sachs, Jeffrey D., Christian Kroll, Guido Lafortune, Guillaume Fuller, and Frank Woelm. 2022. Sustainable Development Report. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009210058.

Samba Sylla, Ndongo. 2024. “Revisiting the Foreign Debt Problem and the “External Constraint” in the Periphery: An MMT Perspective.” Economic Democratic Initiative, 3-4. https://edi.bard.edu/research/notes/revisiting-foreign-debt.

Sokona et al. 2023. Just Transition: A Climate, Energy and Development Vision for Africa. 76. Independent Expert Group on Just Transition and Development. https://justtransitionafrica.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Just-Transition-Africa-report-ENG_single-pages.pdf.

The White House. 2023. “G7 Hiroshima Leaders’ Communiqué. May 20.” https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/05/20/g7-hiroshima-leaders-communique/.

United National Climate Change (UNFCCC). 2024. “COP26 Outcomes: Finance for Climate Adaptation.” https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-glasgow-climate-pact/cop26-outcomes-finance-for-climate-adaptation#Developed-countries-have-pledged-USD-100-billion-a.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2015. Sovereign Debt Workouts: Going Forward. April. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/gdsddf2015misc1_en.pdf.

____. 2023a. “A World of Debt.” https://unctad.org/publication/world-of-debt

____. 2023b. “Trade and Development Report: Growth, Debt and Climate: Realigning the Global Financial Architecture.” https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/tdr2023_en.pdf.

____. 2023c. “Taking Responsibility. Towards a Fit-for-Purpose Loss and Damage Fund.” https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/tcsgdsinf2023d1_en.pdf

United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs (UN DESA). 2023. “The SDG Stimulus – a High Impact Initiative to deliver financing at scale to rescue the SDGs.” September 19. https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.un.org/en/desa/The-SDG-Stimulus&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1712843724534796&usg=AOvVaw2WyzELdh2WX3stQ0n46iyx.

United National Development Programme (UNDP). 2024. “ No Soft Landing for Developing Economies.” https://www.undp.org/publications/no-soft-landing-developing-economies

Vasic-Lalovic, Ivana, Galant Michael and Francisco Amsler. 2024. “A Greater Burden Than Ever Before: An Updated Estimate of the IMF’s Surcharges.” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, April. https://cepr.net/report/a-broader-impact-than-ever-before-an-updated-estimate-of-the-imfs-surcharges/.

Vasic-Lalovic, Ivana, Merling Lara and Aileen Wu. 2023. “The Growing Debt Burdens of Global South Countries: Standing in the Way of Climate and Development Goals.” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research. October. https://cepr.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/The-Growing-Debt-Burdens-of-Global-South-Countries_Standing-in-the-Way-of-Climate-and-Development-Goals-Lalovic_-Merling_-Wu.pdf.

World Bank. 2023a. “International Debt Report 2023.” December. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/02225002-395f-464a-8e13-2acfca05e8f0.

____. 2023b. “International Debt Statistics.” https://databank.worldbank.org/source/international-debt-statistics.

____. 2024. “World Bank Group Statement on Debt Restructuring Agreement for Zambia.” https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/statement/2024/03/26/world-bank-group-statement-on-debt-restructuring-agreement-for-afe-zambia

Zucker-Marques, Marina. 2023. “Winner Takes All – Twice: How Bondholders Triumph, Before and After Debt Restructuring.” Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery. November 16. https://drgr.org/news/winner-takes-all-twice-how-bondholders-triumph-before-and-after-debt-restructuring/

The authors thank Alex Main, Iyabo Masha, David Rosnick and Mark Weisbrot for helpful contributions, suggestions and editorial work.