October 28, 2015

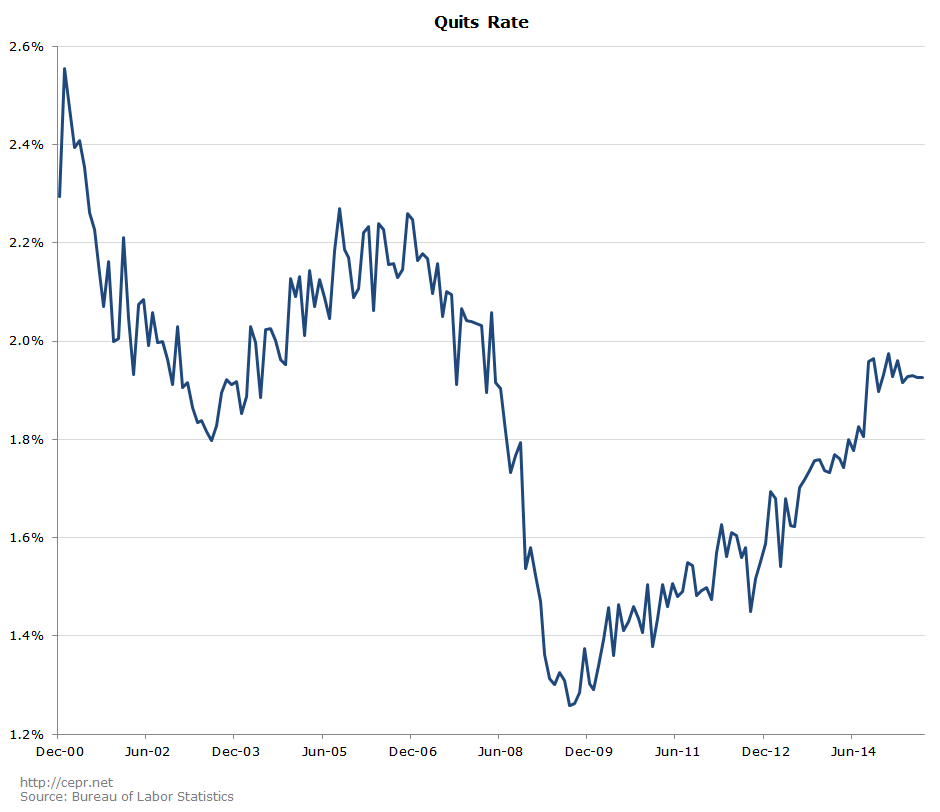

In January 2001, the nonfarm quits rate — the percentage of the nonfarm workforce deciding to leave their jobs in a given month — stood at 2.6 percent. During the recession, the quits rate fell to 1.3 percent; since then, it has mostly but not fully recovered to its pre-recession peak, which itself was lower than the rates seen in the early 2000s:

While “workers quitting their jobs” may sound bad in theory, a high quits rate is actually a signal of a strong labor market. When workers feel that there are few job opportunities available to them, they are less likely to quit their jobs, because they know that they are unlikely to find a new one. Moreover, in a strong job market, employers are more likely to poach workers from other firms by offering them higher wages, which will also cause workers to quit their jobs.

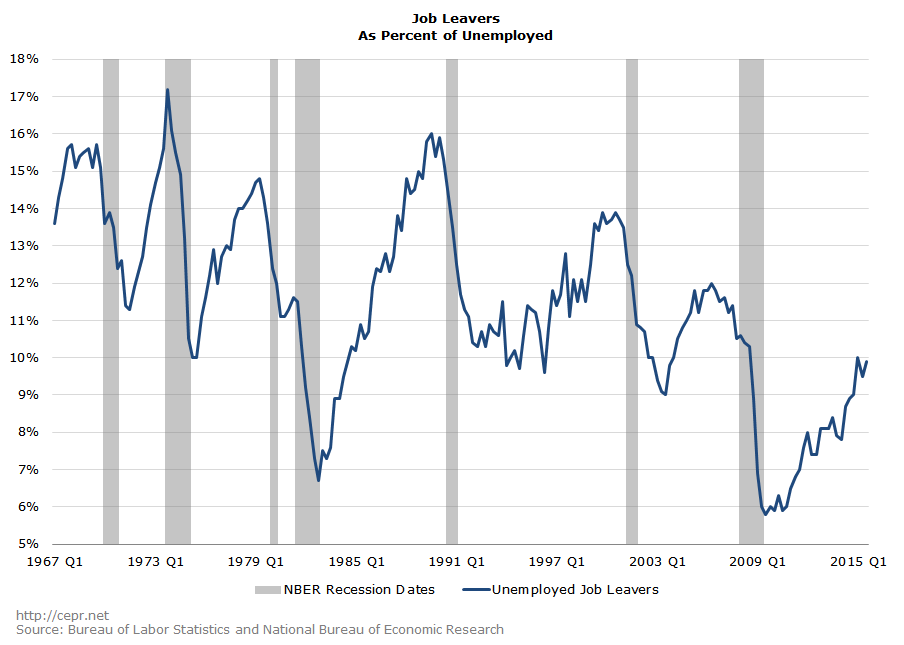

While our data on the quits rate only go back to December of 2000, researchers have access to another measure which gives them a proxy for how many workers are quitting their jobs: the percentage of the unemployed who are out of work because they quit their last job. Such people are referred to as “Job Leavers.” If we look at the historical data, we can see that the unemployed are more likely to be job leavers when the labor market is strong:

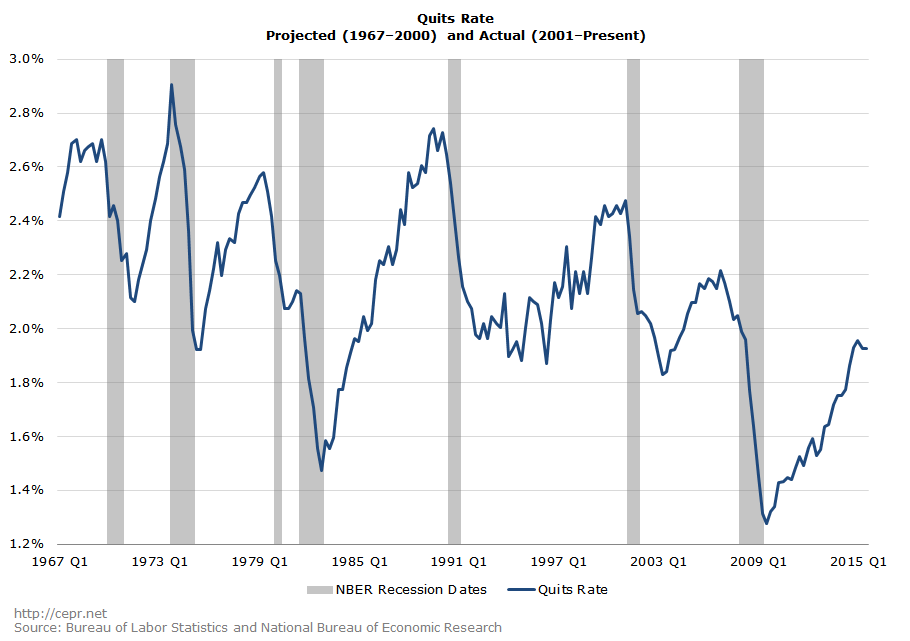

Since the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) first began reporting the quits rate, the correlation between the quits rate and the percentage of unemployment due to quits has been nearly perfect.* It isn’t clear whether or not this is also true for the pre-JOLTS era. But if it is, we can predict that the quits rate for the years 1967–2015 appears as follows:

The quits rate can teach us at least two important lessons about today’s economy. First, this is yet more evidence that the unemployment rate is overstating the degree of recovery. The quits rate in the fourth quarter of 2006 was 2.22 percent, and the share of unemployment due to quits was 11.5 percent. Yet the quits rate for the third quarter of 2015 has so far been just 1.93 percent,** and the share of unemployment due to quits was 9.9 percent. This is significantly better than the third quarter of 2009 (when the quits rate was 1.28 percent and the share of unemployment due to quits was 5.8 percent), but it’s also clearly worse than before the recession.

The second point worth noting is that the quits rate even in the mid-2000s wasn’t particularly high. Between 1967 and 1981, the share of unemployment due to quits never fell below 10.0 percent. At its 1973 fourth-quarter peak, it was as high as 17.2 percent. However, between the first quarter of 2002 and the fourth quarter of 2007, the share of unemployment due to quits averaged just 10.8 percent, and remained in the range of 9.0 to 12.0 percent. This indicates that the labor market had room to tighten even before the economy entered into the recession. If the economy today is supposed to be near full employment — as the Congressional Budget Office and many members of Federal Reserve have argued — most workers haven’t noticed.

*Quits Rate = 0.136 x (Percentage of Unemployment due to Quits) + 0.006. The R-squared value is 0.908.

**JOLTS releases the quits rate on a delayed schedule compared with most other economic data. The 1.93 percent figure shows the quits rate through the first two months of the third quarter.