September 12, 2012

Today’s Census release on Health, Income, Poverty, and Inequality in 2011—what I like to call the annual HIPI report—was not particularly surprising. The best news was that the number of people without health insurance declined by 1.3 million, with the largest gain among adults ages 19-25. The credit here largely goes to the Affordable Care Act.

The bad news was that median household income declined 1.5 percent in real terms from 2010. However, the poverty rate and numbers didn’t really change. It may seem odd that they didn’t move in the same direction—but the big story here was more Americans working full-time, year-round in jobs that don’t pay so hot.

The table below shows what happened. Almost 2.2 million more Americans were working year-round, full-time in 2011 than in 2010. But full-time workers were more likely to be working in poorly compensated jobs. As a result, median income for all year-round, full-time workers fell by a stunning 2.5 percent.

| Number and Incomes of Full-Time, Year-Round Workers: 2010 and 2011 | ||||

| Number (Thousands) | ||||

| 2010 | 2011 | Difference | Percentage Change | |

| Men | 56283 | 57993 | 1710 | 3.0% |

| Women | 43179 | 43663 | 484 | 1.1% |

| Median Income ($) | ||||

| 2010 | 2011 | Difference | Percentage Change | |

| Men | $49,463 | $48,202 | $(1,261) | -2.5% |

| Women | $38,052 | $37,118 | $(934) | -2.5% |

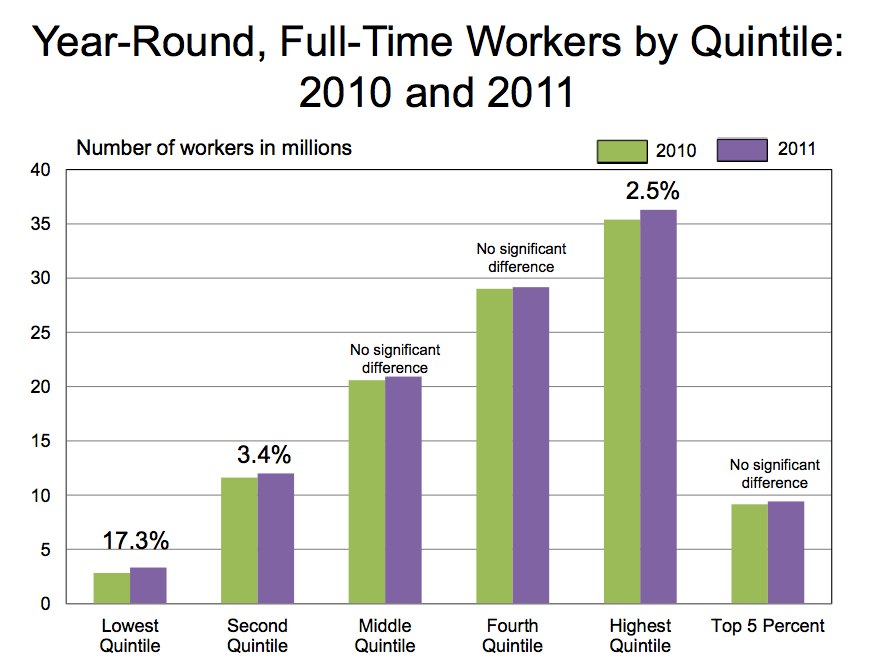

The chart below, from David Johnson’s presentation at the Census news conference, shows the change in number of YRFT workers by income quintile.

As this shows, the growth in full-time, year-round workers happened mostly at the bottom (a 17.3 percent increase) and at the top.

Things would be very different, and much more positive for the middle class and working class, if Congress had passed the American Jobs Act proposed by President Obama in 2011. The Jobs Act would have, among other things, created 1.3 million jobs by the end of 2012, including for several hundred thousand construction workers, teachers, and first responders.

PS: Some economists have argued that basic social insurance programs, like the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP), have operated as a work discincentive. But that claim isn’t supported by the data—the increase in FTYR work came even though more low-income families got help making ends meet from SNAP last year.