January 10, 2024

1. The 2021 SDR issuance is estimated to have saved hundreds of thousands of lives, if we use, e.g., the Bank for International Settlements’ research on the relation between recessions and mortality.

2. Yet the US Treasury Department recently “ruled out a new allocation of IMF Special Drawing Rights resources and said the Fund needed to stick to its core activities of strong surveillance, policy advice and reforms required in its lending.” But the world economy is vastly worse now than it was on August 2 2021 when the SDR issuance was approved by the IMF.

The IMF predicts that global growth will slow to 2.9% in 2024 — less than half that of 2021. Nearly 80 low- and middle-income countries are in or at risk of debt distress. The most recent five-year growth projection from the World Economic Outlook was just 3 percent annually, the lowest projection since 1990. And IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva has recently issued grave warnings about the high risks of global economic shocks, and a lack of a global economic safety net.

3. A new SDR issuance, which would come at no cost to the US taxpayer, could make a significant difference in the US economy in the immediate future, by preventing some of the loss of export-related jobs here, as demand for US exports falls with recessions in other countries.

The US economy lost an estimated 2.2 million export-related jobs (January 2020 to May 2021) due to loss of demand for US exports in the rest of the world because of the pandemic recession. While some of these have since been recovered, the risk of global economic disruption is high. SDRs could help to stabilize the world economy and protect export-related jobs for US workers.

(Reference: Special Drawing Rights Could Help Recover Millions of Export-Related US Jobs, and Create Even More, August 2021. Note also that the International Trade Administration estimates the number of US jobs supported by exports fell by 1.6 million from 2019 to 2020.)[1]

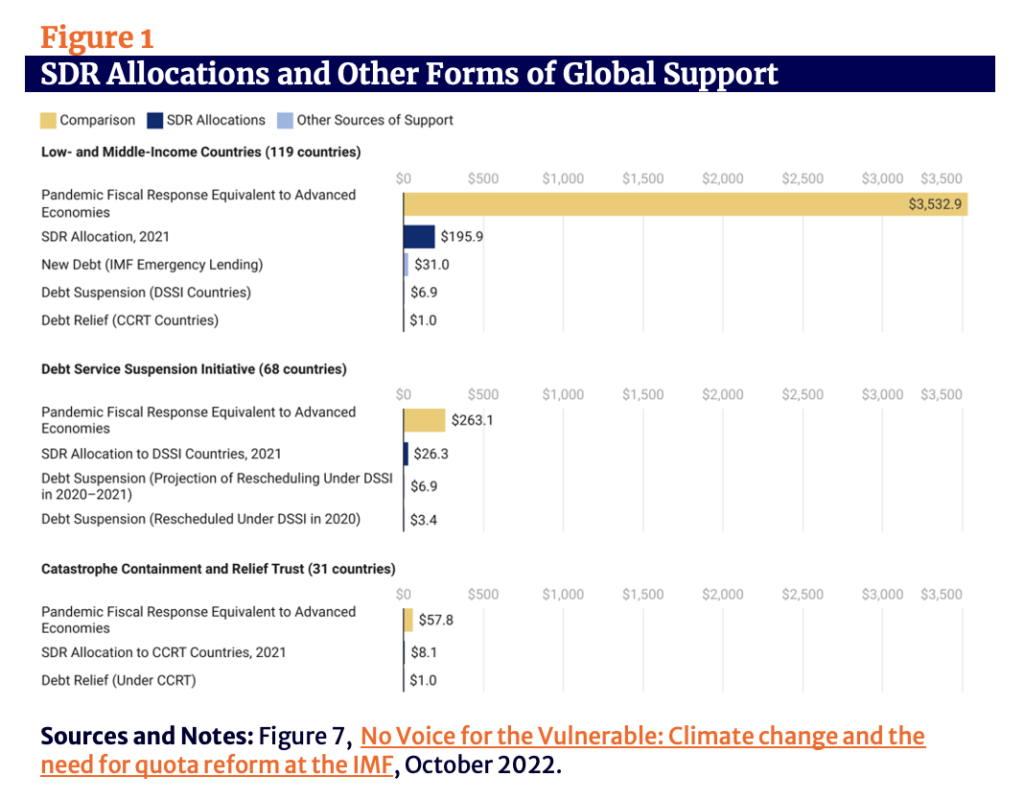

4. The 2021 SDR issuance was by far the largest source of any aid to developing countries in any year since the pandemic.

Figure 1 shows how much larger the SDR allocation is for each group of developing countries, as compared with what was received (often adding to countries’ debt), by countries covered by other initiatives (the Debt Service Suspension Initiative, DSSI; and the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust).

While DSSI countries are eligible for the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments, creditor countries have failed to produce a single debt restructuring agreement through the framework since its launch in 2020.[2] Unlike other forms of support, SDRs do not require any budget expenditures or government appropriations from the United States (or other IMF member countries).

5. SDRs create no debt and have no conditions attached, making them 100 percent net positive, unlike, e.g., IMF or other loans.

This is especially important right now, given the rise in sovereign debt since the pandemic, and very high interest rates faced by developing countries.

As IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva has said:

“Slower growth, high inflation leading to higher interest rates and a stronger dollar also make it harder to reduce high debt levels. Too many low-income countries, and some middle-income countries, are facing crushing debt burdens—again, with massive implications for potential growth and the economic prospects of millions of people.”

6. The US Treasury Department (beginning with former secretary Mnuchin, who immediately killed the proposal for a new allocation of SDRs at the IMF when it was first made by the managing director in March 2020), has made only one argument against an issuance of SDRs: that more than 60 percent of the issuance goes to high-income countries, and that therefore it is more reasonable to “rechannel” those SDRs rather than issue new ones. This argument is deeply flawed:

i. It has been more than 2 years since the last issuance of SDRs and few SDRs have been effectively rechannelled. This is much too slow; 333 million people are now at risk of starvation, up from 135 million before the pandemic and from 276 million at the start of 2022. As soon as Treasury gives the go-ahead to a new SDR issuance, they can be unlocked for transfer to IMF member countries within weeks.

ii. Unlike a new issuance, rechanneling the US’s SDRs requires Congressional approval. In the current Congress, this is extremely unlikely, if not impossible.

iii. There is no waste, creation, or use of resources involved in the SDRs distributed to high-income countries, because they cannot use them (countries must show need in order to convert SDRs to hard currency). China also cannot use them because it has more than $3 trillion in reserves.[3] Only countries that can show need — almost all of which are low- or middle-income — can make active use of the SDR allocation, making a new allocation progressive, regardless of its technical distribution among members.

iv. Perhaps most importantly, the proposed rechanneling would convert SDRs from an international reserve asset that carries no debt and no conditions, to a loan that both creates debt and has conditions attached.[4]

7. There is no downside risk to a new issuance, and no economists have put forth credible economic arguments against an issuance.

8. There is no cost to the US budget or the US taxpayer, at present, or in the future, from a new issuance.

9. IMF-member countries under US sanctions (e.g., Iran, Venezuela, Russia, Myanmar, Belarus, Afghanistan, and Syria) have not been able to access their holdings of Special Drawing Rights.[5]

See figure: SDR Holdings for Member Countries with Sanctioned Central Banks or Unrecognized Governments, August 2021 and July 2022: in Special Drawing Rights One Year Later, By the Numbers, August 2022.

[1] Special Drawing Rights Could Help Recover Millions of Export-Related US Jobs, and Create Even More, August 2021. Note also that the International Trade Administration estimates the number of US jobs supported by exports fell by 1.6 million from 2019 to 2020

[2] See also Special Drawing Rights One Year Later, By the Numbers, August 2022.

[3] See IMF here.

[4] The Case for More Special Drawing Rights: Rechanneling Is No Substitute for a New Allocation, October 2022.

[5] See figure: SDR Holdings for Member Countries with Sanctioned Central Banks or Unrecognized Governments, August 2021 and July 2022: in Special Drawing Rights One Year Later, By the Numbers, August 2022.

[6] Why Is the IMF Collecting Surcharges from Developing Countries?, The Hill, October For more detail, see IMF Surcharges: Counterproductive and Unfair, CEPR, September 2021; and A Guide to IMF surcharges, Eurodad, December 2021.