January 11, 2018

Since the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, the US government has disbursed some $4.4 billion in foreign assistance to the tiny Caribbean nation. At least $1.5 billion was disbursed for immediate humanitarian assistance, while just under $3 billion has gone toward recovery, reconstruction, and development. Since many of the funds have gone toward longer-term reconstruction, there remains some $700 million in undisbursed funding ? in addition to annual allocations.

In our 2013 report “Breaking Open the Black Box,” we found:

Over three years have passed since Haiti’s earthquake and, despite USAID’s stated commitment to greater transparency and accountability, the question “where has the money gone?” echoes throughout the country. It remains unclear how exactly the billions of dollars that the U.S. has spent on assistance to Haiti have been used and whether this funding has had a sustainable impact. With few exceptions, Haitians and U.S. taxpayers are unable to verify how U.S. aid funds are being used on the ground in Haiti. USAID and its implementing partners have generally failed to make public the basic data identifying where funds go and how they are spent.

In response to that report, and others from USAID’s own inspector general and from the Government Accountability Office, the US Congress passed bipartisan legislation (the 2014 Assessing Progress in Haiti Act, or APHA) requiring greater reporting requirements from State and USAID.

These additional reporting requirements, which include information on subcontractors, as well as benchmarks and goals, represent a significant step in the right direction regarding transparency around US foreign assistance. However, limitations remain.

A joint review published in December 2016 by CEPR and the Haiti Advocacy Working Group found that the reports on US assistance in Haiti contain “omissions and deficiencies, including incomplete data, a failure to link projects and outcomes, and a failure to adequately identify mistakes and lessons learned.”

These weaknesses notwithstanding, the congressionally mandated APHA reports provide the most complete picture available of US assistance programs, whether in Haiti or anywhere else in the world, and remain useful especially for organizations on the ground looking to investigate or follow up on specific US-financed programs.

But a recent review of contract and grant information from USASpending.gov shows that USAID, and US foreign assistance generally, is still plagued by many of the same problems that have been evident for years. While USAID has drastically changed its rhetoric about partnering with local organizations and involving local stakeholders in the development of new programs, it does not appear to have made significant changes to its system of allocation of USAID funds. And now, what progress has been made appears threatened.

Some Progress with Local Partners, But the Beltway Bandits are Still on Top

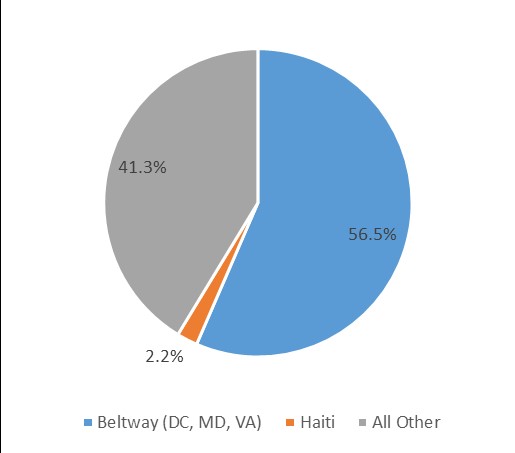

The majority of US assistance to Haiti is through USAID. Since 2010, USAID has disbursed at least $2.13 billion in contracts and grants for Haiti-related work. Overall, just $48.6 million has gone directly to Haitian organizations or firms ? just over 2 percent. Comparatively, more than $1.2 billion has gone to firms located in DC, Maryland, or Virginia ? more than 56 percent, as can be seen in Figure 1. The difference is even starker when looking just at contracts: 65 percent went to Beltway firms, compared to 1.9 percent for Haitian firms.

Figure 1. USAID Awards by Location of Recipient (Percent of Total)

Source: USASpending.gov and authors’ calculations

USAID has made it a priority to involve more local firms and civil society organizations ? holding informational sessions, meetings with stakeholders, etc. While there has been some slight improvement in the amount of funds going directly to Haitian organizations since 2010, the trend has more recently reversed direction.

In 2016, USAID assistance to Haiti was lower than in any year since the earthquake, totaling $140 million. However it was also the year when the greatest amount of USAID funds was allocated directly to Haitian organizations ? more than $15 million. This is primarily due to an increase in Haitian recipients of USAID grants. After totaling just $2.5 million from 2010 to 2014, Haitian grantees received more than $22 million in 2015–2016. A significant portion of this, nearly $6 million, went to Papyrus, a local management company, in order to increase the capacity of local organizations to partner with USAID.

In 2017, however, funds awarded to Haitian organizations were reduced drastically. Only one new grant was initiated with a local partner last year, totaling just $700,000. Though it remains too early to tell if this will continue into 2018, the decrease would appear to be consistent with the Trump administration’s stated “America first” policy.

Though more than $3 million was awarded to Haitian firms in 2017 (via contracts, as opposed to grants), the vast majority of this went to firms conducting evaluations of other USAID projects. Of the $20 million awarded thus far in 2018 by USAID, only $70,000 has gone to Haitian firms.

It would therefore appear that the small progress USAID achieved in partnering directly with local organizations is being reversed under the new US administration.

A key impediment to more fully understanding how USAID funds are administered in Haiti has been the lack of information on subawardees. However greater compliance with APHA reporting requirements over the past few years has produced a significant amount of data at the subaward level. Overall, via the USASpending.gov database, subaward data is available for about 50 prime contracts or grants totaling more than $500 million.

Through those prime contracts, more than $175 million has been awarded to subs, but only about $50 million has gone to local organizations. So, while looking only at prime awardees does understate the full extent of local participation, it is clear that the vast majority of USAID funds don’t go further than the prime awardee, and of those funds that go to subs, less than a third go to Haitian firms.

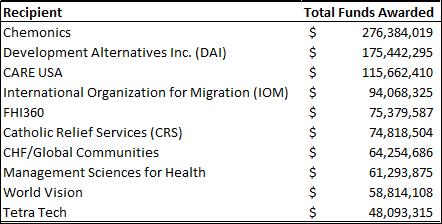

Among the top ten prime awardees, nine are US-based organizations and one is a UN entity, as can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1. Top Ten Recipients of USAID Funding Since Earthquake

Source: USASpending.gov and authors’ calculations

And while there have been changes in USAID recipients over the years, the two largest, Chemonics and Development Alternatives Incorporated (DAI) continue to dominate in Haiti. Since 2016, more than 40 percent of all USAID contract funding has gone to just these two Beltway firms.

US Priorities and Recent Developments: Case Studies

Knowing who received the money is important but it is also worth looking at what types of projects the US has funded in Haiti. Of these, the largest share went toward Health & Disabilities ($1.18 billion), followed by Governance and Rule of Law ($470 million), Food Security ($339 million) and Shelter ($196 million).

Digging deeper, the US has designated four “pillars” of its foreign assistance in Haiti: Infrastructure and Energy; Food and Economic Security; Health and Other Basic Services; and Governance and Rule of Law. Responding to congressional requirements, the State Department now provides objectives and status updates on each “pillar.” Again, there is significant information missing from these reports, but they still have useful data, particularly for groups on the ground.

Next let’s examine examples of recent US contracts and grants in some of these priority areas.

Housing (Pillar A: Infrastructure and Energy)

After the earthquake, the US had an ambitious plan to build thousands of new homes in Haiti. Following drastic cost overruns and changing demands, the US shifted away from building new houses. Instead, the US has provided technical assistance to build the capacity of the housing sector, and with partners is working to provide housing finance. To date, “with USAID financing of $482,000, partner financing institutions have committed over $10 million for loans, with $3.1 million already disbursed for 451 loans,” the State Department reported in August 2017.

But USAID is also continuing to spend millions to make up for its previously failed attempts at new housing construction.

In 2015, two US companies were barred from receiving additional contracts over faulty construction practices at the Caracol EKAM housing site. Studies revealed the companies had used substandard concrete and had overbilled USAID.

In October 2014, USAID awarded a no-bid contract to Tetra Tech (one of the largest US contractors in the country) to determine the extent of the problems with the Caracol EKAM houses and to oversee the repairs. A year later, another US company, DFS Construction, was awarded a contract to repair the houses. The work is ongoing in 2018.

The two contracts for Tetra Tech and DFS have totaled more than $20 million, $4 million of which was awarded in just the last two months of 2017. While USAID has moved on from building new homes, they are still spending millions of dollars correcting previous mistakes.

Ports (Pillar A: Infrastructure and Energy)

Initially, the US had planned on creating a new port in Fort Liberté near the flagship reconstruction development project, the Caracol Industrial Park. The port was one of the many subsidies used to attract a South Korean garment industry firm to the park. USAID spent more than $4 million on feasibility studies for the new port; however, the plans quickly fell apart. The Government Accountability Office determined USAID lacked expertise in the area, underestimated the time it would take to build a new port, and overestimated private sector interest in the project.

In the last few years, the US has shifted course and is now supporting the rehabilitation of the port in Cap-Haïtien, also in the North.

The US is working with the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation and the Haitian government to create a public-private partnership to manage the port. It is expected that a firm will be selected soon.

In late 2015, USAID awarded Nathan Associates (based in Virginia) a contract to enhance the regulatory environment of the port. The ongoing work has thus far cost nearly $7.5 million. Around the same time, AECOM, another US firm, was given more than $1 million for urgent repairs to the port. USAID also awarded more than $3 million to the World Bank and more than $7 million to the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) in support of the project. Finally, at the end of 2016, USAID awarded yet another US firm, the Louis Berger Group, nearly $6 million to perform construction management services for the port’s rehabilitation.

All told, USAID has distributed at least $30 million in support of the port project.

Food Security (Pillar B: Food and Economic Security)

US support for food security in Haiti has predominantly focused on the Feed the Future program, which began just before the earthquake with the WINNER program. Implemented by Chemonics and completed in 2015, WINNER’s total cost was more than $145 million. (The program was the subject of a scathing report by Oxfam International in 2013.)

In 2013, USAID initiated a new Feed the Future program, this time implemented by DAI in the northern part of the country. This program is ongoing and has thus far cost more than $77 million. In its most recent report, the State Department notes that the Feed the Future/North program “is successfully increasing the incomes of thousands of Haitian farmers” despite recent problems due to drought.

A USAID Inspector General (OIG) report from 2015 casts doubt on this finding, however. The program was meant to work with local organizations to increase output; however, the OIG report found that the program was “not achieving these goals.” Most troubling was the failure of DAI to develop the capacity of local organizations, as the program intended. The OIG report points out one of the main impediments of getting Haitian organizations ready to receive USAID funding directly:

[L]ocal organizations also did not have any incentive to become eligible for direct USAID funding. Meeting the Agency’s eligibility criteria was tough and often required significant time and resources. For example, many organizations needed to improve their workspaces and hire additional employees, like accountants, to meet the requirements for separation of duties and internal controls. Many organizations could not afford to do this before first receiving USAID funding—but they could not receive USAID funding until they made the required changes.

While DAI received $77 million from USAID, the data indicates that only about 7 percent of this, or a little over $5 million, went to Haitian firms in the form of subcontracts. Without transitioning responsibilities over to local organizations, however, the sustainability of any advances remains in serious question.

Still, the Feed the Future program continues. In 2015, USAID initiated yet another project, this time aimed at the West Department. Once again, the contract was awarded to Chemonics, which has already received nearly $25 million for the program.

Elections (Pillar D: Governance and Rule of Law)

A primary aspect of US funding in the Governance and Rule of Law pillar concerns elections. Since the earthquake, USAID has spent more than $1 million on election-specific advisors hired by USAID. During the contested election of 2015, the US spent more than $30 million on elections, though as HRRW reported at the time, much of that went to US-based or international organizations in support of the elections, not toward the election itself.

When an independent commission recommended redoing those 2015 elections due to massive irregularities, the US pulled about $1.7 million in funding from the UN-administered “basket fund” used to support elections. Overall, the US awarded $3 million to the Organization of American States for its observation mission, $8 million to the “basket fund,” more than $12 million to UNOPS for election logistics, and $16 million to IFES and the National Democratic Institute.

The electoral process is now over, but USAID has continued to allocate funding toward elections. The priority now is to help create a permanent electoral council to oversee elections (provisional electoral councils have managed each of Haiti’s elections since its return to democracy).

In January 2017, before current president Jovenel Moïse had even assumed office, USAID hired an election advisor on a two-year contract for more than $300,000.

In June of the same year, USAID awarded a $6.75-million grant to the Consortium for Election and Political Process Strengthening. The consortium had already received nearly $25 million since the earthquake, despite questionable progress on the electoral front.

But there is a significant difference with the consortium now that a Republican holds the presidency in the US. The consortium is composed of two organizations. One, IFES, remains the same. The other, however, has changed. Whereas money previously was awarded to the National Democratic Institute (NDI) through the consortium, in 2017 NDI was replaced by the International Republican Institute (IRI).